The views expressed in this paper are those of the writer(s) and are not necessarily those of the ARJ Editor or Answers in Genesis.

Abstract

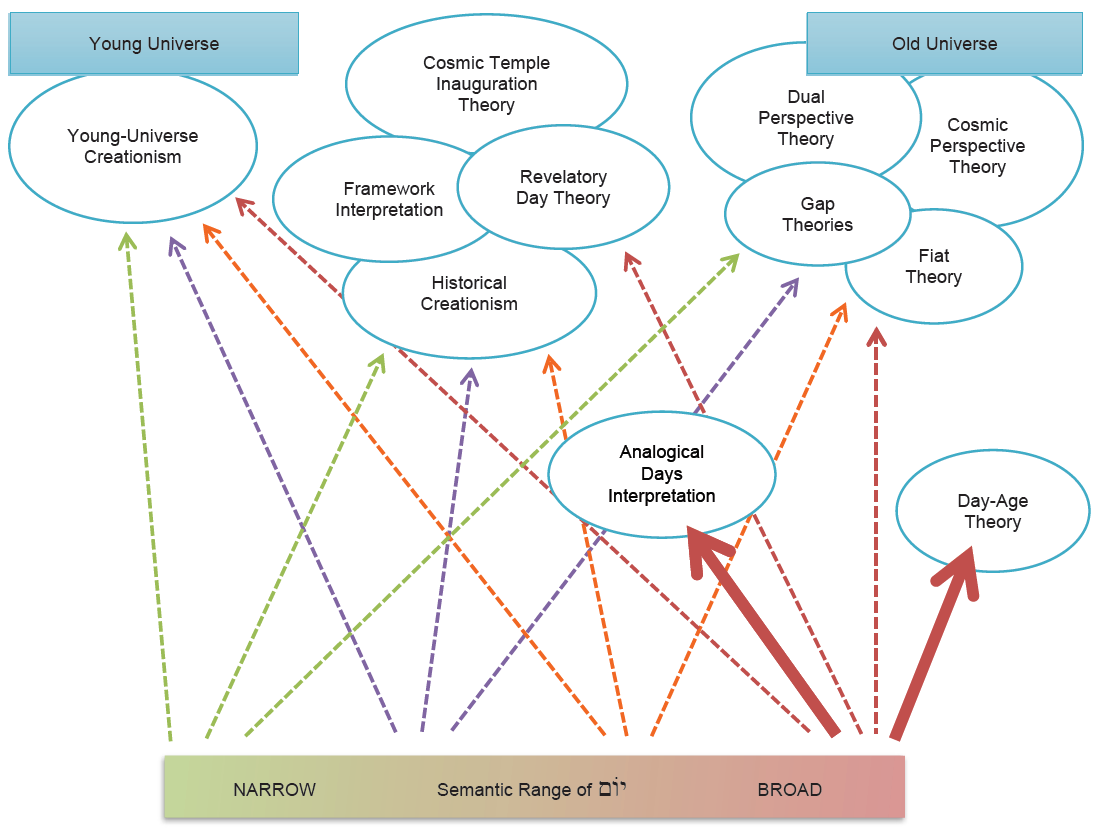

Before the Enlightenment, most theologians believed the earth was created in the space of a literal week, a notable exception (among others) being Augustine, who interpreted the days of creation figuratively. Most believed that the universe began sometime between approximately 3600 BC and 7000 BC. However, between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries—with the growing acceptance of geological uniformitarianism and, later, Darwinian evolution—an increasing number of eminent scholars advocated a multi-billion-year-old universe and questioned the validity of the biblical account. In order to accommodate billions of years into the Genesis account of origins, theologians proposed a range of new interpretations. Some, such as the Gap Theory, sought to retain a literal understanding of יוֹם. Others, particularly the Day-Age Theory, maintained that the term had a broad semantic range that could include a sense of vast periods of time. Over the past two centuries, the issue of the meaning of יוֹם in relation to the age of the universe has been vigorously debated by many scholars, though ignored as irrelevant by others.

Following an introductory survey of the biblical, historical and theological, and linguistic contexts of this issue, the study looks at delineations and definitions of יוֹם in Scripture, and in lexical and other sources. The central analysis examines how the semantic range of יוֹם has been discussed in the context of the creation account and in relation to the age of the universe, both historically, and, more particularly, by 40 scholars (or teams of scholars) over the past 50 years. It is evident that a great variety of opinion exists regarding the semantic range of יוֹם. It is also clear that there is a considerable disconnection between lexicography regarding יוֹם and the formation of creation theology. Most respected lexical sources do not allow for a broad semantic range for יוֹם, yet many theologians believe it to be rather flexible.

Prologue

I am very thankful for having had the opportunity to do this study, which was facilitated through the guidance of Drs. Richard E. Averbeck and Eric J. Tully at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

I acknowledge with gratitude the kind granting of permission by Robert I. Bradshaw for inclusion of his data regarding early Jewish and Christian views on the length of the days of creation (see page 105).

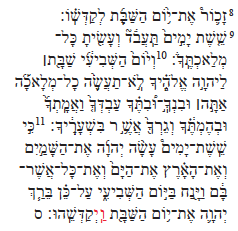

Hebrew Bible quotations are taken from the text of the 1997 second edition of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (based on the Leningrad Codex B19A), as found in Accordance and BibleWorks, “which has been edited over the years to bring it into greater conformity with the Leningrad Codex” (BibleWorks, WTT Version Info). Both the Accordance and BibleWorks versions of BHS include the 2010 WTM Release 4.14.

Unless indicated otherwise, all Scripture translations into English are my own rendering.

Unless stated otherwise, all instances of emphasis within a quotation are those of the cited author. I have indicated wherever I have added my own emphases, except in the case of Scripture quotations. My preferred means of emphasis is italics. If the quotation already contains italics, then I resort to underlining (and specify so). Additionally, even where the quotation does not contain italics, I sometimes still use underlining for the sake of consistency with underlining in other nearby quotations.

Introduction

This work examines how scholars’ perceptions of the semantic range of יוֹם have affected their discussions of the age of the universe. While each of the key elements in this relationship—the semantic range of יוֹם and the age of the universe—have indeed been studied before, I am not aware of any other study that specifically focuses on the interaction between the two, across a range of scholarly works.

The subject of creation and origins is popular and is often vigorously debated. A key element of enquiry and discussion within this topic is the age of the universe. Some scholars feel that the Bible does not speak to the question of the age of the universe. Certainly, the Bible does not make any outright statement like, “The universe was created by God x thousand or million or billion years ago.” However, other scholars believe that the biblical text does indeed give indications concerning the age of the universe. In their interactions with the text, many such scholars make reference to the Hebrew word יוֹם usually translated “day,” which occurs fifteen times in the thirty-five verses of the Genesis creation account (Genesis 1:1–2:4). This work examines (1) how scholars have understood the semantic range of יוֹם —whether as always having a narrow, restricted sense, or as having a broad range of meanings across different contexts, or as somewhere in between these two extremes—and (2) how these perceptions have affected their discussions of the age of the universe. Must the word יוֹם always indicate a normal day, or can it refer to a longer period of time? Does its flexibility or inflexibility of meaning have anything relevant to say regarding the age of the universe according to the Genesis account of creation?

There are several reasons why this subject might be viewed as important. Within the Christian church there has been much discussion, sometimes heated and confused, on the issues of creation and, in particular, the age of the universe. It is often asked what the word יוֹם could potentially mean in Genesis. It would be helpful to gain a degree of clarity on the breadth of views regarding the semantic range of יוֹם —including those of lexicographers, theologians, and other scholars—and the kind of reasoning employed in their discussions of יוֹם with respect to the age of the universe. All of this could potentially aid people in making better-informed decisions about how they see the place of יוֹם within the creation debate, and in better understanding those with different opinions from their own.

Outside the Christian Church, many people view the Bible as irrelevant or unreliable, especially when it comes to science. Even some biblical scholars believe that the Genesis account of creation has little, if anything, that is pertinent or authoritative to say regarding modern science. The biblical word יוֹם in the creation account can be seen as irreconcilable with the prevailing view of origins. This work may help people understand the various ways that some biblical scholars, by engaging with the semantic range of the word יוֹם, have explained the Genesis account of creation as being relevant to the issue of the age of the universe.

This third part of the larger work presents the core of the study, the analysis of the works of forty scholars (or teams of scholars) published in (or translated into) English over the past fifty years, which mention the semantic range of יוֹם with reference to the age of the universe. The sources include monographs, creation theologies, Genesis commentaries, contributions to creation debates, and other scholarly works. Key data extracted from these works are tabulated in Appendix 1. Preceding the central analysis is a brief historical survey of interpretation, to show how the semantic range of יוֹם has been understood since biblical times, particularly in relation to the age of the universe. Then, reflection is made upon the findings of the central analysis, highlighting some of the main links, patterns, and trends in the relationships between scholars’ perceptions of the semantic range of יוֹם, and their discussions of the age of the universe. Finally, I draw salient conclusions from throughout the study.

יוֹם in Discussions of the Age of the Universe

The temporal focus of this study is 1967–2017. But before analyzing how יוֹם has been handled in discussions pertaining to the age of the universe over the past fifty years, we will briefly survey the history of interpretation of the days in the creation account prior to 1967.

Brief Historical Survey of Interpretation Prior to 1967

Old Testament Period

According to mainline conservative tradition, Genesis was written by Moses in the latter half of the fifteenth century BC (or a couple of centuries later, according to advocates of a late date for the exodus).1 Elsewhere in the Pentateuch (Exodus 20:11, 31:17), references to the time frame of creation use the same kind of terminology, viz., שֵֽׁשֶׁת־יָמִים֩ (“six days”) followed by a day of rest. While a number of scholars see the Exodus references as strong evidence that the days of creation are literal days, others are not convinced. Nevertheless, however we may understand the term, we can at least assert that Moses was consistent in using the word יוֹם in relation to the time frame of creation.

Throughout the rest of the Old Testament no further reference is made explicitly to the six days of creation, but neither is any alternative timescale mentioned. Thus, for approximately 1,500 years (or 1,300 years if following a late date for the Exodus) from the composition of Genesis up to the time of Jesus, there is no explicit biblical evidence that Israelites regarded the time frame of creation as being anything other than an ordinary week. If, as proponents of an old universe argue, Jewish tradition understood the term יוֹם to mean something other than an ordinary day, or understood there to be vast eons between or following the days of creation, such a tradition is lacking explicit evidence in the rest of the biblical canon.

New Testament Period

While there has been much debate about the form and completeness of genealogies in both Old and New Testaments, a straightforward reading of Luke 3:23– 38 links Jesus all the way back to “Adam, the son of God” (v. 38). Taken together with Jesus’ declaration about marriage partners, “But from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female’” (Mark 10:6), this certainly gives the impression that Jesus and Luke regarded the creation of everything, including humans, as having taken place about eighty generations earlier. If there is another explanation, it is not immediately obvious. Moreover, while nothing explicit is mentioned by Jesus or the New Testament writers concerning their interpretation of יוֹם in Genesis 1, neither do they give any indication that they interpreted the days of creation in anything other than their ordinary sense. Terry Mortenson (2008, 342) concludes, “There is nothing in [Jesus’] teachings that would support an old-earth view (that Adam was created long ages after the beginning of creation).”

Regarding the common reckoning of a day in the New Testament period, D. A. Carson (1991, 156–157, underlining added) comments,

Counting the hours from midnight to noon and noon until midnight … is alleged to be the ‘Roman’ system, unlike the Jewish system which counts from sunrise to sunset (roughly 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m.). But the evidence in support of a Roman system for counting hours turns out to be unconvincing. The primary support is from Pliny the Elder; but all he says is that Roman priests and authorities, like the Egyptians, counted the official day, the civil day, from midnight to midnight—useful information in leases and other documents that expire at day’s end. Nowhere does he suggest that any of his contemporaries count the hours of a day from midnight; indeed, he says that ‘the common people everywhere’ think of the day running from dawn to dark. Jews, Romans and others divided the daylight ‘day’ into twelve hours.

2 Peter 3:8b (and Psalm 90:4)

Advocates of a broad semantic range for “day” very often point to Peter’s allusion (in 2 Peter 3:8b) to Psalm 90:4. Because of the ubiquity of this line of reasoning, and because of its relevance to this thesis, I will discuss it below in some detail.

In the Greek Bible, the phrase χίλια ἔτη (“a thousand years”) is found together with ὡς (“as”) only in LXX Ps 89:4 (equivalent to HB 90:4), and in 2 Peter 3:8b. In Psalm 90:4 (LXX 89:4) Moses writes, “For a thousand years in Your eyes are as yesterday when it passes, or a watch in the night,” and the apostle comments, “With the Lord one day is as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day” (ESV).

James L. Kugel (2007, 50) explains—with reference to the problem of both the six-day time frame in Genesis 1, and God’s promise in Genesis 2:17 that Adam would die on the day that he ate of the forbidden fruit—that, for some,

The answer suggested by Ps. 90:4 was that the days mentioned in the creation of the world were days of God, a thousand-year unit of time known to Him and quite independent of the sun. The world was thus really created over a period of six thousand years. This idea is alluded to in a number of ancient texts: apparently, it simply became common knowledge that a ‘day of God’ lasts a thousand years.

In support of this notion, in addition to 2 Peter 3:8b, Kugel (2007, 50) cites the following:

- “For with Him a ‘day’ signifies a thousand years,” Letter of Barnabas 15:4

- “Adam died … and he lacked seventy years of one thousand years [that is, he died at the age of 930]. One thousand years are as a single day in the testimony of heaven; therefore it was written concerning the tree of knowledge, ‘On the day that you eat of it, you will die,’” Jubilees 4:29–30

- “It was said to Adam that on the day in which he ate of the tree, on that day he would die. And indeed, we know that he did not quite fill up a thousand years. We thus understand the expression ‘a day of the Lord is a thousand years’ as [clarifying] this,” Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 81:3.

While the phraseology and context of the latter three clearly demonstrate that the authors interpretively equated “day” with “a thousand years,” the same cannot so readily be said of 2 Peter 3:8b, particularly when read in light of Psalm 90:4.

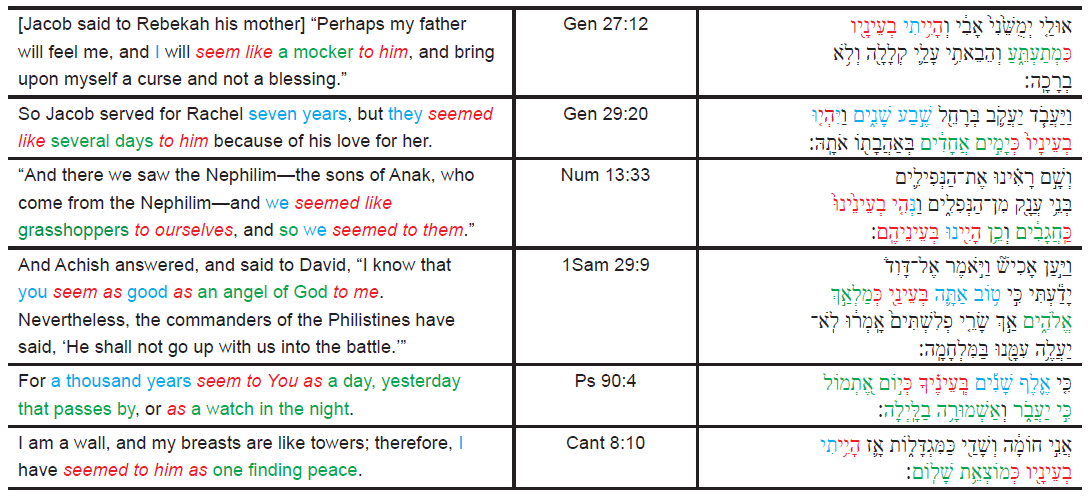

The precise phraseology in Psalm 90:4, בְּעֵינֶיךָ כְּ, leaves little doubt that the language being employed is figurative. The formula, היה) בְּעֵינַיִם כְּ)—lit., “to be in [someone’s] eyes as/like [something/someone],” i.e., “to seem as/like [something/someone to someone]”—occurs six times in the Old Testament to provide an analogy for how somebody experienced or felt something (see Table 1).

Table 1. Occurrences of the formula היה) בְּעֵינַיִם כְּ), “to seem as/like [something/someone to someone].”

For example, in describing the depth of Jacob’s love for Rachel, Genesis records, “Jacob served for Rachel seven years, but they seemed like several days to him because of his love for her” (Genesis 29:20). Upon returning from their scouting trip into Canaan, the fearful spies reported to the people of Israel, “And there we saw the Nephilim—the sons of Anak, who come from the Nephilim—and we seemed like grasshoppers to ourselves, and so we seemed to them” (Numbers 13:33). Of course no one would suggest that the Israelites were really grasshoppers or that seven years equates to a few days. The phrase היה) בְּעֵינַיִם כְּ) is not an equation (contrary, for example, to the wording of the Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Hierosolymitanus versions of the Letter of Barnabas 15:4, “For with Him a ‘day’ signifies [σημαίνει] a thousand years”). Rather, it is a linguistic tool for conveying how something is valued, or feared, or regarded, by comparing it with something else. So, for instance, Jacob’s love for Rachel was so intense that working for Laban for seven years was a small price to pay in return for marrying her; in his estimation it felt like it was as easy as just a few days of work. And the trepidatious Israelites were so fearful of the giants they had seen in Canaan that they felt powerless and incapable of confronting them; from their perspective—and indeed also from the perspective of the giants themselves—they were as insubstantial as grasshoppers.

So returning to Psalm 90:4 it seems that Moses is not attributing the word יוֹם with the value of “one thousand years,” as Barnabas does in his letter. The context of Psalm 90 is the fragile nature of mortal man compared to the powerful, eternal nature of God: “Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever You had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting You are God. You return man to dust and say, ‘Return, O children of man!’” (Psalm 90:2–3, ESV*). We may live for seventy or eighty years, Moses says, yet the fleeting lives we value so much are filled with toil and trouble (v. 10). But for an eternal God, a millennium seems but a brief span of time.

To this thought Peter adds another, that “with the Lord one day is as a thousand years.” For an omnipotent God, unimaginable feats can be accomplished in what we would regard as an impossibly short time frame. Furthermore, God pays great attention to all of the intricate happenings of His creation, second by second. He cares about the details. Indeed, Peter adds, “The Lord is not slow to fulfill His promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance” (v. 9).

Psalm 90:4 and Peter’s second clause in 2 Peter 3:8b are like a telescopic perspective on God’s majestic power and mind-boggling, eternal nature. Peter’s first clause is like a microscopic view, focusing right down to the smallest details that matter to God.

Neither verse seems to impinge upon the semantic range of “day” or “year.” Henri Blocher ([1979] 1984, 45) explains, “In Psalm 90:4 … ‘day’ has its most commonplace meaning, but it is used in a comparison and that is what brings out the relativity of human time for God (as also in 2 Peter 3:8).” יוֹם is no more equal to a millennium than Jacob’s seven years were equal to a few days, or than the Israelites were to grasshoppers.

Others scholars have drawn attention to the misapplication of these verses for the purpose of positing a broad semantic range for יוֹם. For instance, Whitcomb (1973, 68) writes,

Note carefully that the verse does not say that God’s days last thousands of years, but that “one day is with the Lord as a thousand years.” In other words, God is completely above the limitations of time in the sense that he can accomplish in one literal day what nature or man could not accomplish in thousands of years, if ever. Note that one day is “as a thousand years,” not “is a thousand years,” with God. If “one day” in this verse means a long period of time, then we would end up with the following absurdity: “a long period of time is with the Lord as a thousand years.” Instead of this, the verse reveals how much God can accomplish in a 24-hour day, and thus sheds much light upon the events of Creation Week.

Morris (1974, 226–227) argues,

The familiar verse in II Peter 3:8 … has been badly misapplied when used to teach the day-age theory. In the context, it teaches exactly the opposite, and one should remember that “a text without a context is a pretext.” Peter is dealing with the conflict between uniformitarianism and creationism prophesied in the last days. Thus, he is saying that, despite man’s naturalistic scoffings, God can do in one day what, on uniformitarian premises, might seem to require a thousand years. God does not require aeons of time to accomplish His work of creating and redeeming all things.

Kulikovsky (2009, 149) explains, “Rather than defining the meaning of ‘day,’ these verses [Psalm 90:4 and 2 Peter 3:8] are similes which indicate that God is eternal, is not constrained by time, and does not experience the passage of time as humans do.”

From the Early Church Period until the Twentieth Century

Much has already been written on the history of interpretation of the days of creation in Genesis since the time of the church fathers. Here we will briefly make some general observations, before surveying a range of modern perspectives from prominent and respected scholars leading up to 1967.

In his introduction to The Days of Creation: A History of Christian Interpretation of Genesis 1:1–2:3, the culmination of “nine and a half long years of study” (Brown 2014, ix), Andrew J. Brown (2014, 3) suggests,

The opening part of Genesis has been not only (probably) the most commented-on written text in human history, but also one of the greatest influences on Western thought over the last two millennia, and if we want to avoid a gaping ignorance about the course of Western history, thought and culture, not to mention Christian theology and the formation of the sciences concerned with origins, we simply cannot afford to ignore this particular interpretive story.

Brown’s book “examines the history of Christian interpretation of the seven-day framework of Genesis 1:1–2:3 in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament from the post-apostolic era to the debates surrounding Essays and Reviews (1860)” (back-cover blurb). He describes this history as “a story of difference,” and he laments the oversimplification of “the interpretive ‘playing fields’ of the past” by some scholars, in an “attempt to line up past thinkers behind a modern … viewpoint” (284). Brown (284) cites two opposing sets of debaters in The Genesis Debate: Three Views on the Days of Creation,2 as making what he describes as “sweeping” or “blanket generalization[s]” about historic interpretation in order to support their respective positions.3 The “‘difference’ in hermeneutical landscapes,” Brown (285) argues, “makes it incumbent upon us to study the history and thinking of the different eras concerned, in aid of a better-informed appreciation of their approaches to this and other biblical texts.”

Others have expressed a similar desire for greater judiciousness in approaching the history of interpretation of Genesis 1. For example, John Millam (2011) bemoans, “Most attempts to use the church fathers by both old-earth and young-earth creationists are seriously flawed, just in different ways.” Although Millam defends an old-earth position, he acknowledges that he appreciated the “lucid and well-documented” introduction by the young-earth advocate Robert I. Bradshaw (1999) in his work Creationism and the Early Church. Millam (2011) explains, “What I found so refreshing and educational about Bradshaw’s work was that rather than simply cataloging the church fathers according to their interpretations, he analyzed the complex history and undercurrents behind their views.” Indeed, under the heading, “The Use and Abuse of Church History,” Bradshaw (1999) begins the first chapter of his book by stating, “A great deal of effort has been expended in recent years by all sides in the debate over the biblical view of origins setting about what the early church believed to be the correct interpretation of Genesis 1–11…. The result has been that a number of often contradictory positions have all been presented as ‘the early church’s view.’”

Notwithstanding Brown’s important point about ‘difference,’ and the need to avoid generalizations, neither would it be helpful, or true, to imply that all modern viewpoints were represented equally in earlier times. Thus, Brown’s (285, emphasis added) statement, “Non-literal interpretations of the days of Genesis formed a sustained minority strand throughout the period in view in this study,” is roughly compatible with Feinberg’s (2006, 597, emphasis added) assessment, “Though at various times in church history some questioned whether the days of creation were literal solar days, the predominant view at least until the 1700s was that the days of creation were six twenty-four-hour days. Both Luther and Calvin held this position.”

Early Writings

In his chapter on “The Early Church and the Age of the Earth,” Bradshaw (1999) tabulates “how the writers of the early church [and other early writers] viewed the days of creation” (see Table 2). In nearly half of those he lists, their view of the length of the days of creation is not explicitly stated. Of the rest, nine out of thirteen (69%) advocate literal days, with four (31%) preferring a figurative interpretation. While Bradshaw admits, “We cannot be sure of the views of most writers for a variety of reasons,” he opines, “My own view based upon the style of exegesis of other passages of Scripture would lead me to think that the vast majority of those listed as having an unclear view would opt for 24 hours had they discussed the subject.”

Notwithstanding these important statistical observations, theological discussions are ideally to be evaluated objectively on the merits of each position, not merely by the quantity of adherents of a particular perspective. Indeed, history (including church history) has repeatedly demonstrated that a majority may, at times, be wrong. Thus, scholars pay attention not only to how many advocates a particular position has, but also specifically who the advocates are, and whether or not they are deemed reliable.

| Writer | Date | 24 hours | Figurative | Unclear | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philo | ca. 20 BC–ca. AD 50 | ✓ | Creation, 13 | ||

| Josephus | AD 37/38–ca. 100 | ✓ | Antiquities, 1.1.1 (1.27–33) | ||

| Justin Martyr | ca. 100–ca. 165 | ✓ | |||

| Tatian | 110–180 | ✓ | |||

| Theophilus of Antioch | ca. 180 | ✓ | Autolycus, 2.11–12 | ||

| Irenaeus of Lyons | ca. 115–202 | ✓ | |||

| Clement of Alexandria | ca. 150–ca. 215 | ✓ | Miscellanies, 6.16 | ||

| Tertullian | ca. 160–ca. 225 | ✓ | |||

| Julius Africanus | ca. 160–240 | ✓ | |||

| Hippolytus of Rome | 170–236 | ✓ | Genesis, 1.5 | ||

| Origen | 185–253 | ✓ | Celsus, 6.50, 60 | ||

| Methodius | died 311 | ✓ | Chastity, 5.7 | ||

| Lactantius | 240–320 | ✓ | Institutes, 7.14 | ||

| Victorinus of Pettau | died ca. 304 | ✓ | Creation | ||

| Eusebius of Caesarea | 263–339 | ✓ | |||

| Ephrem the Syrian | 306–373 | ✓ | Commentary on Genesis, 1.1 | ||

| Epiphanius of Salamis | 315–403 | ✓ | Panarion, 1.1.1 | ||

| Basil of Caesarea | 329–379 | ✓ | Hexameron, 2.8 | ||

| Gregory of Nyssa | 330–394 | ✓ | |||

| Gregory of Nazianxus | 330–390 | ✓ | |||

| Cyril of Jerusalem | died 387 | ✓ | Catechetical Lectures, 12.5 | ||

| Ambrose of Milan | 339–397 | ✓ | Hexameron, 1.10.3–7 | ||

| John Chrysostom | 374–407 | ✓ | |||

| Jerome | 347–419/420 | ✓ | |||

| Augustine of Hippo | 354–430 | ✓ | Literal, 4.22.39 |

For instance, for those who believe in a figurative interpretation of יוֹם in the creation account, the relative scarcity of support for their position among the early church fathers is counterbalanced by the theological giant, Augustine. Significantly, in this regard, Frank Robbins (1912, 64; quoted in Brown 2014, 59) notes, “Augustine was ‘the chief authority of the medieval Latin writers on creation,’ and his treatment of the sequence of creation days was the most influential one to emerge from the patristic era.” R. J. Bauckham (1999, 300) makes reference (albeit in a different context) to “that extraordinary weight of influence that only Augustine has had on Western theology.” Jaroslav Pelikan (1971, 1:292– 293) asserts even more forcefully,

There is probably no Christian theologian—Eastern or Western, ancient or medieval or modern, heretical or orthodox—whose historical influence can match his…. In a manner and to a degree unique for any Christian thinker outside the New Testament, Augustine has determined the form and the content of church doctrine for most of Western Christian history.

Not surprisingly, therefore, many proponents of a non-literal interpretation of יוֹם in the creation account have enlisted Augustine in support of their theses. For example,

- Henri Blocher ([1979] 1984, 49): “Augustine … constructed a brilliant and startling interpretation of the days in De Genesi ad litteram. In his view, their temporal character is not physical but ideal”;

- Dick Fischer (1990, 15–16): “Many of the early church fathers took their clues from Scripture alone in the scarcity of natural evidence. Irenaeus, Origen, Basil, Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, to name a few, argued that the days of creation were long periods of time”;

- R. Laird Harris (1995, 22): “Long ago Augustine had held that the days were periods of indefinite length”;

- N. H. Ridderbos (1957, 11): “[The] view [that the arrangement of seven days is intended as a literary form] was already current in the early Church (Philo of Alexandria, Origen, Augustine)”;

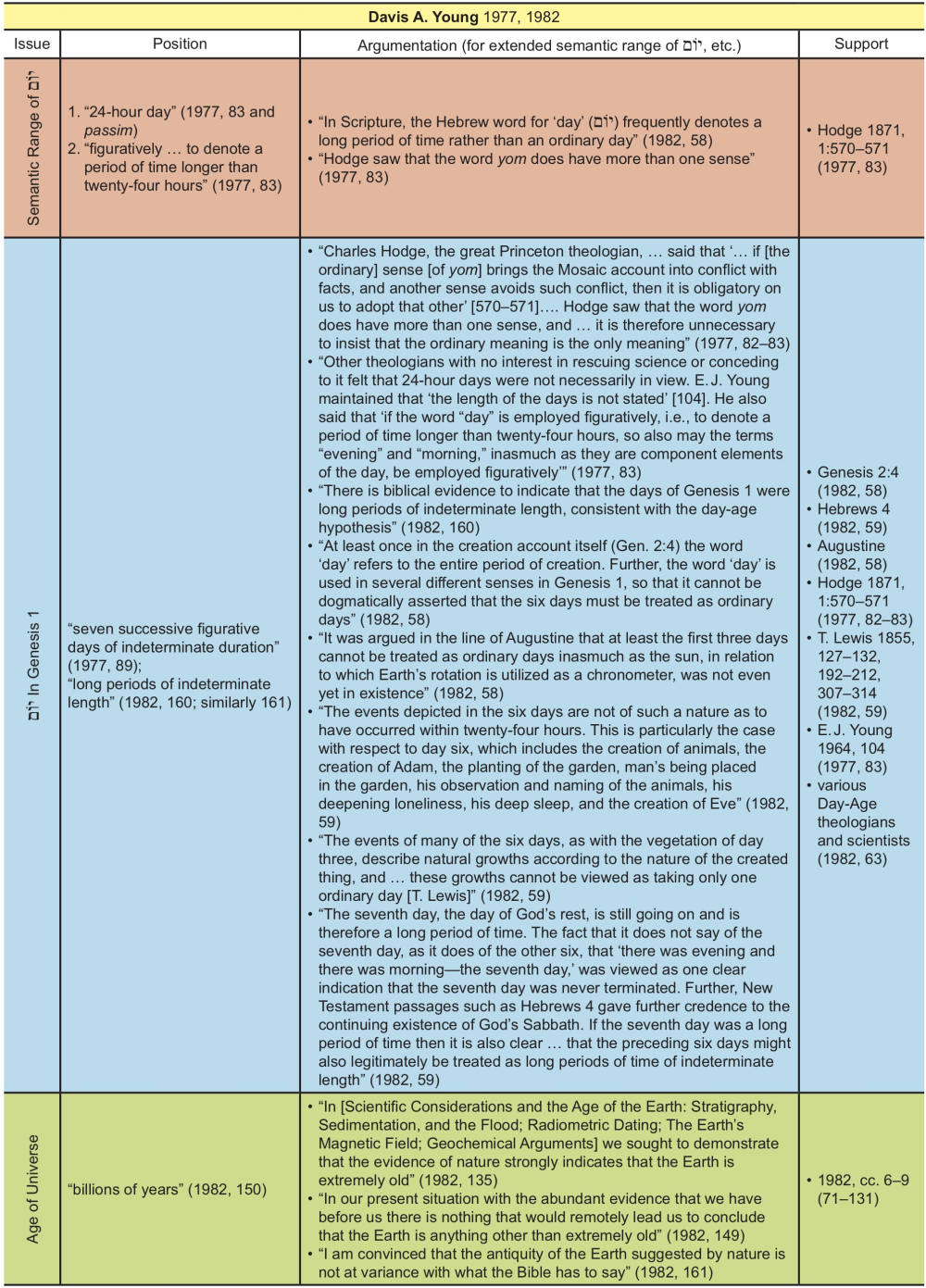

- Davis A. Young (1982, 58): “It was argued in the line of Augustine that at least the first three days cannot be treated as ordinary days inasmuch as the sun, in relation to which Earth’s rotation is utilized as a chronometer, was not even yet in existence.”

Augustine, as others, had a multi-layered approach to the interpretation of Scripture, including the literal (by which he meant historical) sense, and also the allegorical meaning (cf. Ortlund 2017). He believed that God’s creation was instantaneous, and that the word “day” was employed pedagogically, in order to aid our understanding. As such, he was “taking the days as a kind of framework or literary device” (Ortlund 2017). Augustine reasoned:

- Being omnipotent, God would not need longer than an instant to create everything, and certainly would not require as long as six days. In the Latin version that Augustine read of the Wisdom of Sirach (or Book of Ecclesiasticus), which he regarded as canonical, it states, “He Who lives for eternity created all things at once [simul]” (18:1).

- The creation account does not seem to present ordinary days, since (a) the sun was not created until the fourth day, (b) the word “day” is used differently in Gen 2:4, and (c) Gen 2:5a appears to preclude a straightforward chronological reading.

The Middle Ages and the Reformers

In his “Treatise on the Work of the Six Days,” Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225–74) asserts regarding יוֹם אֶחָד in Genesis 1:5b, “The words ‘one day’ are used when day is first instituted, to denote that one day is made up of twenty-four hours. Hence, by mentioning ‘one,’ the measure of a natural day is fixed” (Aquinas 1947). In summing up the Middle Ages, Brown (2014, 102) observes,

Frank Robbins characterized medieval exegesis of the Hexaemeron as a gradual defection from Augustine’s abstractness …

Thomas Aquinas’ decision not to endorse Augustine’s viewpoint perhaps constituted a turning point. The literal sense was clearly coming into favour in the later centuries, and was destined to prevail in the era of the Reformation, and not only among Reformers.4

With regards, specifically, to Martin Luther, Brown (2014, 111) notes, “Augustine’s Literal Meaning seems to Luther a fundamentally allegorical or figurative understanding. The Reformation emphases on the clarity of Scripture and the priesthood of all believers implied that God did not intend the Genesis accounts to be comprehensive only to an intellectual elite. Augustine is implicitly reproved for his presumption.” In his Lectures on Genesis, Luther (1958, 1:5; quoted in Brown 2014, 111–112) argues,

If, then, we do not understand the nature of the days or have no insight into why God wanted to make use of these intervals of time, let us confess our lack of understanding rather than distort the words … We assert that Moses spoke in the literal sense, not allegorically or figuratively, i.e., that the world, with all its creatures, was created within six days, as the words read. If we do not comprehend the reason for this, let us remain pupils and leave the job of teacher to the Holy Spirit.

Some modern scholars are nervous of accepting Luther’s literal approach to creation because of reservations about some of his other beliefs. Against Luther’s reliability in such matters—where a literal reading of the Bible seemingly clashes with scientific observation—Lennox (2011, 17) notes, “It is alleged that … Martin Luther … rejected the heliocentric point of view in rather strong terms in his Table Talk (1539).” However, Lennox (2011, 18) admits, “There is considerable debate about the authenticity of this quote.” Furthermore, as neither theologians nor scientists are right all of the time, evidence and testimony regarding each interpretive dilemma ought to be weighed separately in any attempt to arrive at the truth.

Like Aquinas several centuries earlier, Calvin (n.d., s.v. “Gen 1:5”) uses the occasion of commenting on Gen 1:5b to affirm the literal sense of יוֹם:

Here the error of those is manifestly refuted, who maintain that the world was made in a moment. For it is too violent a cavil to contend that Moses distributes the work which God perfected at once into six days, for the mere purpose of conveying instruction. Let us rather conclude that God himself took the space of six days, for the purpose of accommodating his works to the capacity of men.

Moving into the seventeenth century, but prior to the “nascent scepticism” that would soon take hold with the flourishing of biblical criticism, Brown (2014, 132–133) notes,

The literal interpretation of the creation week reached a peak in British Protestant interpretation of the early seventeenth century ... This dominant literalism was the offspring of the overwhelmingly literal example of continental Protestants. It was normal for Protestant Genesis commentaries from around this time, both British and continental, to emphasize the six-day span of creation. In time this usage was adopted, probably thanks to Calvin’s influence, into creedal documents such as the Irish Articles of Religion (1615), compiled by James Ussher, and subsequently in the Westminster Confession, finalized in 1648.

Hitherto, the vast majority of historians and theologians held that the age of the universe was to be measured in thousands of years. In his monumental four-volume work, A New Analysis of Chronology and Geography, History and Prophecy, William Hales listed over one hundred and twenty different opinions regarding the date of creation, ranging from 6,984 BC to 3,616 BC (see Table 3). Given that the modern consensus accepts an age in terms of billions of years, it is ironic that Hales regarded the comparatively tiny discrepancy of over three millennia as a “disgraceful discordance” (1830, 1:214).

| Originator (date, where specified) | Source | Date of Creation |

|---|---|---|

| Alphonsus (AD 1252) | Muller | 6984 BC |

| Strauchius | 6484 BC | |

| Indian Chronology | Gentil. | 6204 BC |

| Arab. records | 6174 BC | |

| Babylonian Chronology | Bailly | 6158 BC |

| Chinese Chronology | Bailly | 6157 BC |

| Egyptian Chronology | Baillyg | 6157 BC |

| Persian Chronology | Bailly | 5507 BC |

| Eutychius (AD 937) | Univ. Hist. | 5500 BC |

| Eusebius (AD 315) | Uni. Hist. | 5200 BC |

| Bede (AD 673) | Strachius | 5199 BC |

| Justin Martyr (AD 140) | Playfair | 5000 BC |

| Origen (AD 230) | 4830 BC | |

| Usher, Lloyd, Simpson, Spanheim, Calmet, Le Chais, Balir, etc. | 4004 BC | |

| Kepler | Playfair | 3993 BC |

| Bullinger | 3969 BC | |

| Melanchton | Playfair | 3964 BC |

| Luther | 3961 BC | |

| Lightfoot | 3960 BC | |

| Strauchius | 3949 BC | |

| Jerom (AD 392) | Uni. Hist. | 3941 BC |

| Rabbi Lipman | Uni. Hist. | 3616 BC |

Modern Interpreters Prior to 1967

As discussed earlier, the Enlightenment occasioned a significant challenge to traditionally held beliefs. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, increasingly bold voices raised major doubts and objections concerning the Bible. Alternative readings of Genesis 1, such as the Gap Theory and the Day-Age Theory, were put forward. It is in this climate of interpretive pluralism, and fundamentalist backlash, that we begin our survey of modern perspectives on the days of creation.

In 1871, Charles Hodge (1797–1878), “the great Princeton theologian, … as solidly Scriptural as anyone” (Young 1977, 82–83),5 made the following significant contribution:

Admitting the facts to be as geologists would have us to believe, two methods of reconciling the Mosaic account with those facts have been adopted. First, some understand the first verse to refer to the original creation of the matter of the universe in the indefinite past, and what follows to refer to the last reorganizing change in the state of our earth to fit it for the habitation of man. Second, the word day as used throughout the chapter is understood of geological periods of indefinite duration.

In favour of this latter view it is urged that the word day is used in Scripture in many different senses … sometimes for an indefinite period …

It is of course admitted that, taking this account by itself, it would be most natural to understand the word in its ordinary sense; but if that sense brings the Mosaic account into conflict with facts, and another sense avoids such conflict, then it is obligatory on us to adopt that other. Now it is urged that if the word “day” be taken in the sense of “an indefinite period of time,” a sense which it undoubtedly has in other parts of Scripture, there is not only no discrepancy between the Mosaic account of the creation and the assumed facts of geology, but there is a most marvellous coincidence between them. (Hodge 1871, 1:570–571)

But then, in 1878, Robert L. Dabney (1820–98) objected to what he described as the “most fashionable … theory of six symbolic days,” in which each day “is symbolical of a vast period” (Dabney [1878] 1972, 254). In the fifth of his six objections, Dabney (255) reasons,

It is freely admitted that the word day is often used in the Greek Scriptures as well as the Hebrew (as in our common speech) for an epoch, a season, a time. But yet, this use is confessedly derivative. The natural day is its literal and primary meaning. Now, it is apprehended that in construing any document, while we are ready to adopt, at the demand of the context, the derived or tropical meaning, we revert to the primary one, when no such demand exists in the context.

In 1881, the conservative German Lutheran Old Testament commentator, C. F. Keil (1807–88) wrote,

The account of the creation, its commencement, progress, and completion, bears the marks, both in form and substance, of a historical document in which it is intended that we should accept as actual truth, not only the assertion that God created the heavens, and the earth, and all that lives and moves in the world, but also the description of the creation itself in all its several stages. (Keil [1881] 2006, 1:23)

Regarding, specifically, the days of creation, Keil ([1881] 2006, 1:32, 43) reckoned, “if the days of creation are regulated by the recurring interchange of light and darkness, they must be regarded not as periods of time of incalculable duration, of years or thousands of years, but as simple earthly days…. The six creation-days, according to the words of the text, were earthly days of ordinary duration.”

In 1903, the respected conservative theologian Benjamin B. Warfield (1851–1921) wrote, “The conflict as to the age of man on earth is not between Theology and Science … It is between two sets of scientific speculators, the one ... [using] physics … and the other … biology. Theology as such has no concern in this conflict and may stand calmly by and enjoy the fuss and fury of the battle” (Warfield 1903, 241–252; quoted in Warfield 2000, 227). Similarly, in 1911, he stated, “The question of the antiquity of man is … a purely scientific one, in which the theologian as such has no concern” (Warfield 1911, 11). According to Mark A. Noll and David N. Livingstone (2000, 14), “One of the best-kept secrets in American intellectual history [is that] B. B. Warfield, the ablest modern defender of the theologically conservative doctrine of the inerrancy of the Bible, was also an evolutionist.” However, Fred G. Zaspel (2017, 971) counters, “The claim that Warfield held to theistic evolution goes beyond the evidence,” explaining, “Warfield did not endorse theistic evolution as it is understood and advocated today” (953). He notes, “Warfield asserted in 1916 that he had left theistic evolution behind him years earlier” (972).6 Zaspel (2010, 211) concludes, “The prevailing understanding of Warfield as an evolutionist must be rejected.”

In commenting on “Calvin’s Doctrine of the Creation” in 1915, Warfield (1915, 190–255, 196) observed, “The six days he, naturally, understands as six literal days; and, accepting the prima facie chronology of the Biblical narrative, he dates the creation of the world something less than six thousand years in the past.” But Warfield suggests that Calvin believed Moses “accommodated himself to [the] grade of intellectual preparation [of men at large], and confines himself to what meets their eyes” (196). He further posits,

Calvin doubtless had no theory whatever of evolution; but he teaches a doctrine of evolution…. [But] his doctrine of evolution is entirely unfruitful. The whole process takes places [sic] in the limits of six natural days. That the doctrine should be of use as an explanation of the mode of production of the ordered world, it was requisite that these six days should be lengthened out into six periods,—six ages of the growth of the world. Had that been done Calvin would have been a precursor of the modern evolutionary theorists. (209)

It would seem from this that Warfield viewed the semantic range of יוֹם as flexible enough to stretch to a period longer than a day, even an age.

Augustus H. Strong (1836–1921) wrote, “The Scriptures recognize a peculiar difficulty in putting spiritual truths into earthly language … Words have to be taken from a common, and to be put to a larger and more sacred, use, so that they ‘stagger under their weight of meaning’—e.g., the word ‘day,’ in Genesis 1” (Strong [1886] 1907, 35). Strong (393–394) outlines his position as follows:

We adopt neither (a) the allegorical, or mythical, (b) the hyperliteral, nor (c) the hyperscientific interpretation of the Mosaic narrative; but rather (d) the pictorial-summary interpretation,—which holds that the account is a rough sketch of the history of creation, true to all its essential features, but presented in a graphic form suited to the common mind and to earlier as well as to later ages…. This general correspondence of the narrative with the teachings of science, and its power to adapt itself to every advance in human knowledge, differences it from every other cosmogony current among men.

He reacts to a literal interpretation of יוֹם in this way:

The hyperliteral interpretation would withdraw the narrative from all comparison with the conclusions of science, by putting the ages of geological history between the first and second verses of Gen. 1 … To this view we object that there is no indication, in the Mosaic narrative, of so vast an interval between the first and the second verses; that there is no indication, in the geological history, of any such break between the ages of preparation and the present time (see Hugh Miller, Testimony of the Rocks, 141–178); and that there are indications in the Mosaic record itself that the word “day” is not used in its literal sense; while the other Scriptures unquestionably employ it to designate a period of indefinite duration. (Strong [1886] 1907, 394; underlining added)

In 1909, C. I. Scofield (1843–1921) first published his famous reference Bible. A few of his remarks concerning the creation account were to prove immensely influential over the course of the ensuing decades, including advancing the Gap Theory, which was “enormously popularized” by a mere footnote (Fields 1976, ix). Concerning the semantic range of יוֹם, Scofield ([1909] 1917, 4) asserted,

The word “day” is used in Scripture in three ways: (1) that part of the solar day of twenty-four hours which is light (Gen. 1. 5, 14; John 9. 4; 11. 9); (2) such a day, set apart for some distinctive purpose, as, “day of atonement” (Lev. 23. 27); “day of judgment” (Mt. 10. 15); (3) a period of time, long or short, during which certain revealed purposes of God are to be accomplished, as “day of the Lord.”

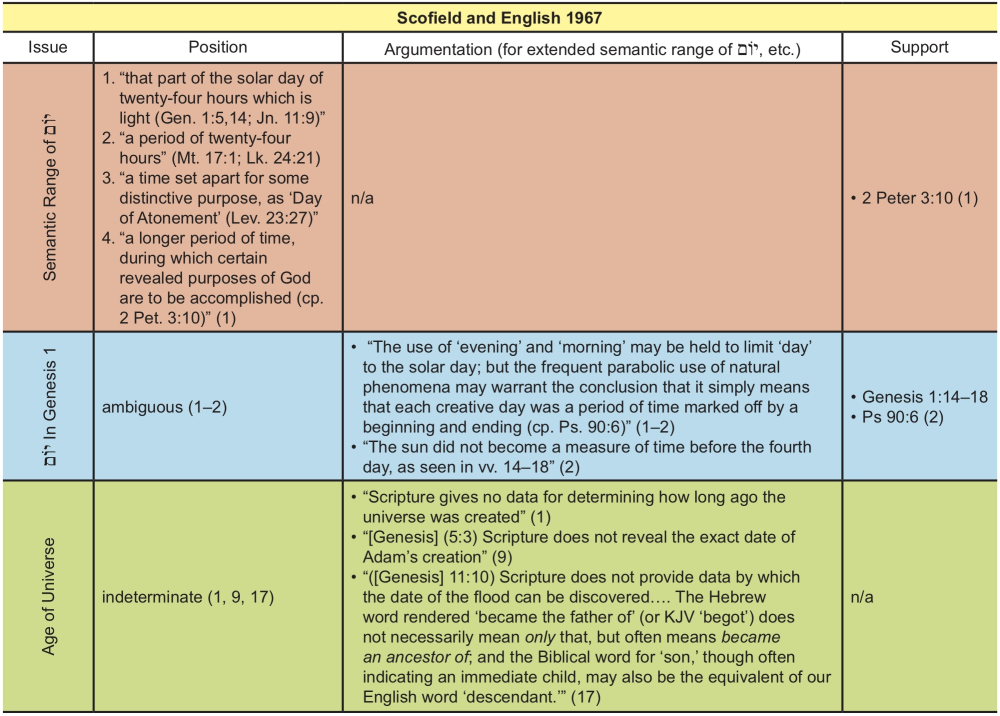

This definition was modified slightly in the 1967 edition of the Oxford NIV Scofield Study Bible, edited by E. Schuyler English:

The word “day” is used in Scripture in four ways: (1) that part of the solar day of twenty-four hours which is light (Gen. 1:5,14; Jn 11:9); (2) a period of twenty-four hours (Mt. 17:1; Lk. 24:21); (3) a time set apart for some distinctive purpose, as “Day of Atonement” (Lev. 23:27); and (4) a longer period of time, during which certain revealed purposes of God are to be accomplished (cp. 2 Pet. 3:10). (Scofield and English 1967, 1)

In his 1930 Genesis commentary, John Skinner (1851–1925) opposed the idea of יוֹם standing for a long age. Instead, he advocated a plain sense reading: “The interpretation of יום as æon, a favourite resource of harmonists of science and revelation, is opposed to the plain sense of the passage, and has no warrant in Heb. usage (not even Ps. 904)…. If the writer had had æons in his mind, he would hardly have missed the opportunity of stating how many millenniums each embraced” (Skinner 1930, 21).

In 1942, Leupold (1942, 57) cites Skinner when arguing for a literal reading of יוֹם in the creation account in his commentary on Genesis:

There ought to be no need of refuting the idea that yôm means period. Reputable dictionaries like Buhl, B D B or K. W. know nothing of this notion. Hebrew dictionaries are our primary source of reliable information concerning Hebrew words. Commentators with critical leanings utter statements that are very decided in this instance [e.g., Skinner, Dillmann]…. There is one other meaning of the word “day” which some misapprehend by failing to think through its exact bearing: yôm may mean “time” in a very general way, as in 2:4 beyôm, or Isa. 11:16; cf. B D B, p. 399, No. 6, for numerous illustrations. But that use cannot substantiate so utterly different an idea as “period.” These two concepts lie far apart.

Nevertheless, Wilbur M. Smith (1894–1976) proceeded to assert quite the opposite in his 1945 apologetics book:

First of all, we must dismiss from our mind any conception of a definite period of time, either for creation itself, or for the length of the so-called six creative days. The Bible does not tell us when the world was created. The first chapter of Genesis could take us back to periods millions of years antedating the appearance of man….

In the second place, we must disabuse ourselves of the idea that these six periods of creation corresponded to our “day” of twenty-four hours. Some still hold this view, but it certainly is not necessary, and the fact that the word day in the Old Testament, even in the first three chapters of Genesis carries many meanings other than that of a period of twenty-four hours, give us perfect freedom in considering it here as an unlimited, though definite period. (Smith 1945, 312)

The same year, Karl Barth (1886–1968) published Volume III, Part 1, of Die Kirchliche Dogmatik, on the subject of The Doctrine of Creation: The Work of Creation. His writings were later to be commandeered by Dutch theologian N. H. Ridderbos (1909–2007) in defense of the Framework Hypothesis (Ridderbos 1957, 12–16). Ridderbos argued, “Regarding the ‘days,’ according to Barth one must think of days of twenty-four hours; but this does not mean that Barth believes the world to have been in fact created in six such days” (15).

According to Louis Berkhof (1873–1957), by the late 1940s his Systematic Theology was “used as a textbook in many Theological Seminaries and Bible Schools” in the USA (Berkhof [1941/1949] 1979, 5). It is significant, therefore, at least with regards to this study, that, while he favors a “literal interpretation of the term ‘day’ in Gen. 1,” (154) in his discussion he admits,

The Hebrew word yom does not always denote a period of twenty-four hours in Scripture, and it is not always used in the same sense even in the narrative of creation. It may mean daylight in distinction from darkness, Gen. 1:5, 16, 18; daylight and darkness together, Gen, 1:5, 8, 13 etc.; the six days taken together, Gen. 2:4; and an indefinite period marked in its entire length by some characteristic feature, as trouble, Ps. 20:1, wrath, Job 20:28, prosperity, Eccl. 7:14, or salvation II Cor. 6:2. (152–153)

In 1948 Lewis Sperry Chafer (1871–1952) was more equivocal:

Genesis clearly declares that there were six successive days in which God created the heavens and the earth of today. The best of scholars have disagreed on whether these are literal twenty-four-hour periods or vast periods of time…. A literal twenty-four-hour period seems to be implied when each is measured by words like, ‘And the evening and the morning were the first day,’ etc. On the other hand, it is reflected in nature that much time has passed since the forming of material things, and the Bible does use the word day symbolically when referring to a period of time. (Chafer 1948, 108–109; underlining added)

The Day-Age advocate Edwin K. Gedney (1950, 51), a science professor with master’s degrees in geology, wrote in 1950,

The students of the last century put much study upon the uses of the word [“yom”], for it was the basis for the chief difficulty in the controversy between the Biblical and scientific accounts. They quickly discovered that the word may be interpreted in a number of ways….

With this orientation we may proceed to suggest a harmony of Genesis with geological facts and with recent geological speculation.

Indeed, in his article on “Genesis” in The New Bible Commentary, E. F. Kevan (1953, 77) noted in 1953,

A … view … held by many at the present time … is that each ‘day’ represents, not a period of twenty-four hours, but a geological age. It is pointed out that the sun, the measurer of planetary time, did not exist during the first three days; further, that the term ‘day’ is used in [Gen] ii. 4 for the whole sixfold period of creation; and that in other parts of Scripture the word ‘day’ is employed figuratively of a time of undefined length, as in Ps. xc. 4.

According to John W. Haas Jr. (1979, 177), Ramm’s 1954 book, The Christian View of Science and Scripture, was “a pivotal event for evangelicals concerned with the relation between science and Christian faith.” Regarding יוֹם Ramm (1954, 222) wrote,

The problem of the meaning of yom is not fully decided as to whether it can mean period or not. The word is one which has many uses as we have already indicated. We are not presently persuaded that it can be stretched so as to mean period or epoch or age, as such terms are used in geology. Though not closing the door on the age-day interpretation of the word yom, we do not feel that lexicography of the Hebrew language will as yet permit it.

However, he concludes, “We believe that the six days are pictorial-revelatory days, not literal days” (Ramm 1954, 222).

Though Ramm was “a progressive creationist,” and “not a theistic evolutionist” (293), he nevertheless suggests, “Evolution may be entertained as a possible secondary cause or mediate cause in biological science” (280). His book evidently provoked a strong reaction from literal creationists, but was received positively by many.7 For instance, writing in A Bernard Ramm Festschrift in 1979, Richard T. Wright (1979, 195) testified that Ramm’s book affirmed his belief in evolution, adding, “I think it is safe to say that today the majority of Christian biologists have accepted the evolutionary hypothesis as God’s creative method, and have successfully integrated it into their theistic world view. Much of the credit for this can certainly be traced to Ramm’s book.”

However, in 1961, John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris published their seminal work, The Genesis Flood: The Biblical Record and Its Scientific Implications. Here they deal very briefly with the days of creation, asserting, “Since God’s revealed Word describes … Creation as taking place in six ‘days’ and since there apparently is no contextual basis for understanding these days in any sort of symbolic sense, it is an act of both faith and reason to accept them, literally, as days” (Whitcomb and Morris 1961, 228). The authors point to an earlier article by Morris “for a brief summation of Biblical evidence that these ‘days’ are intended to be understood literally,” and among several additional corroborating sources they include Berkhof’s Systematic Theology.

While finding “strong reasons for taking the word [yôm] literally in [the] particular context” of Genesis 1, D. F. Payne (1964, 8) nevertheless conceded in a 1962 lecture in Cambridge, United Kingdom, “Those who make the ‘days’ aeons can reasonably claim that the word yôm is often used figuratively in the Old Testament.” The same year, Buswell II Jr. (1962, 1:141) reasoned,

Since the material which is narrated in stages of six “days” in chapter one is all summarized as having taken place “in the day that Jahweh God made the earth and the heavens” in 2:4, it would seem quite obvious and clear that the author uses the word “day” in a figurative sense, just as we often do in modern English, and as the Hebrew prophets did in such expressions as “the day of the Lord,” etc….

When we say that the word “day” is used figuratively, we mean that it represents a period of time of undesignated length and unspecified boundaries, merging into other “days” or periods.

How יוֹם Has Been Handled in Discussions Pertaining to the Age of the Universe over the Past Fifty Years

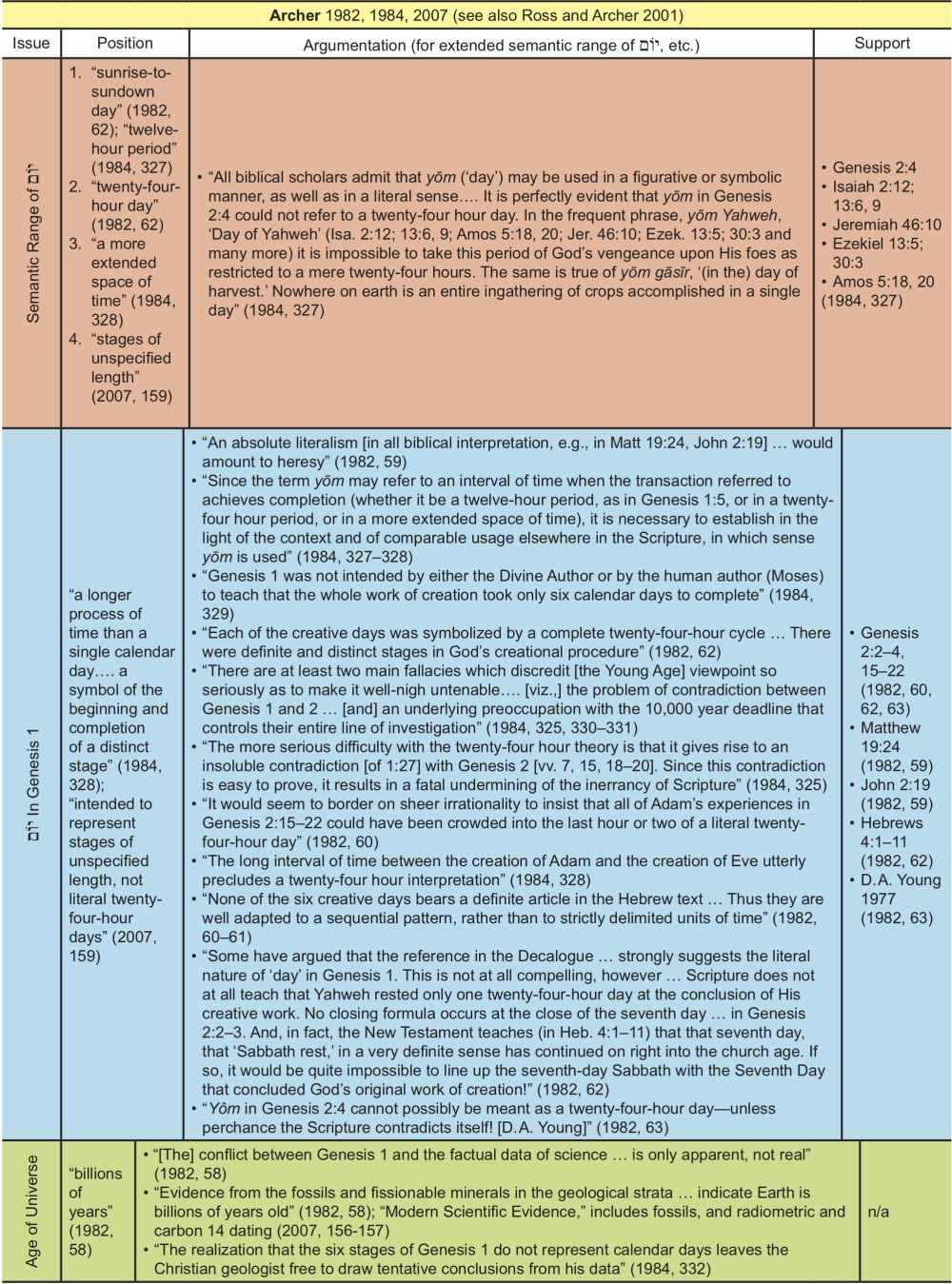

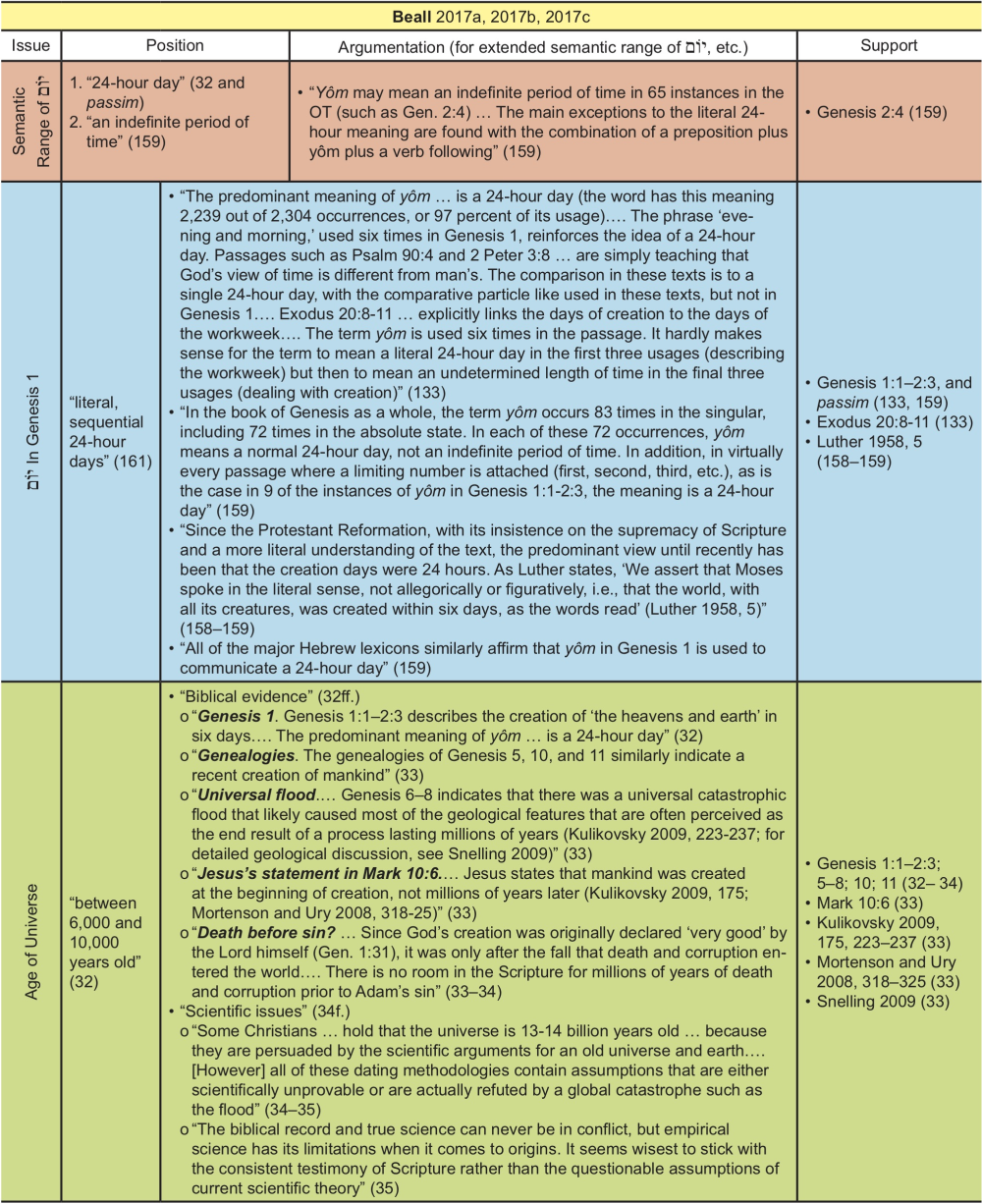

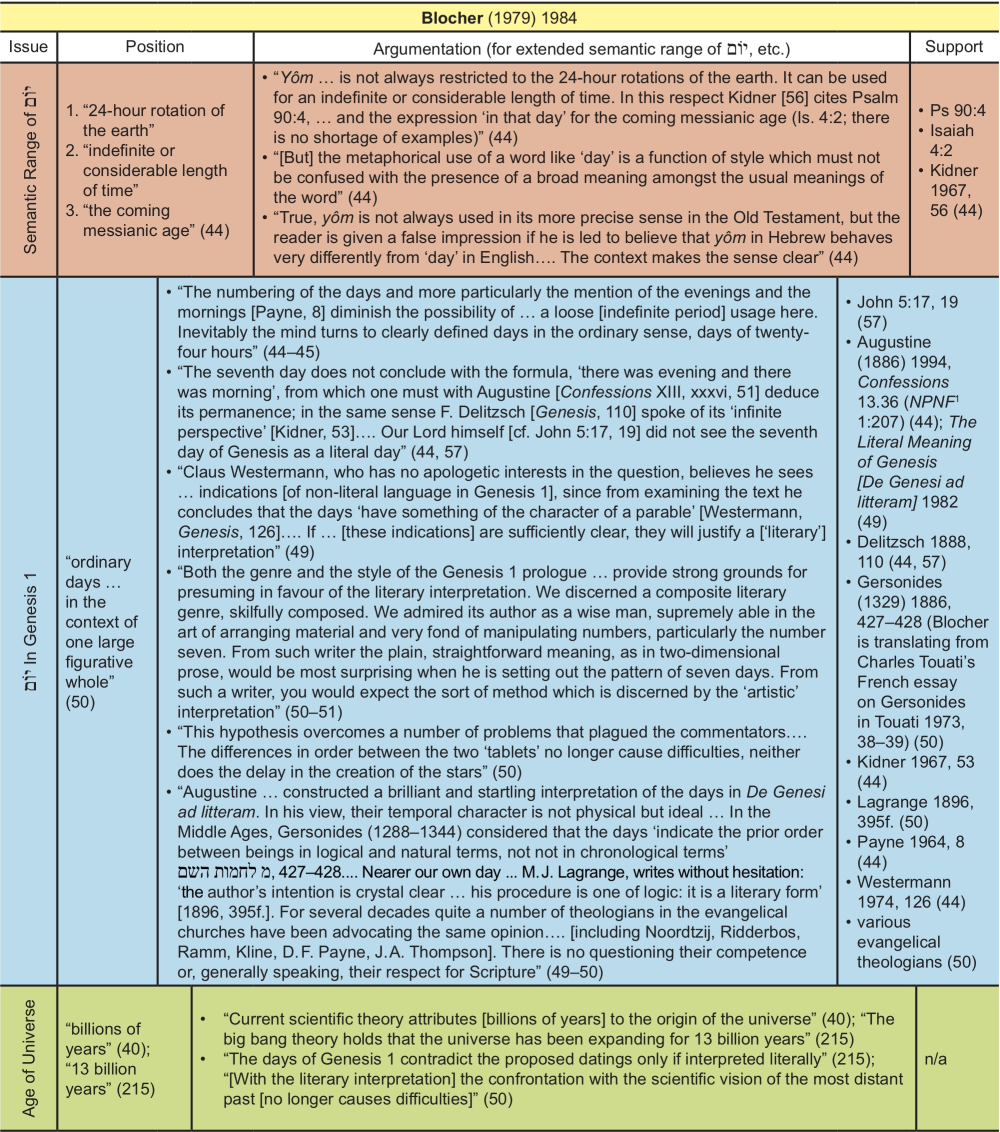

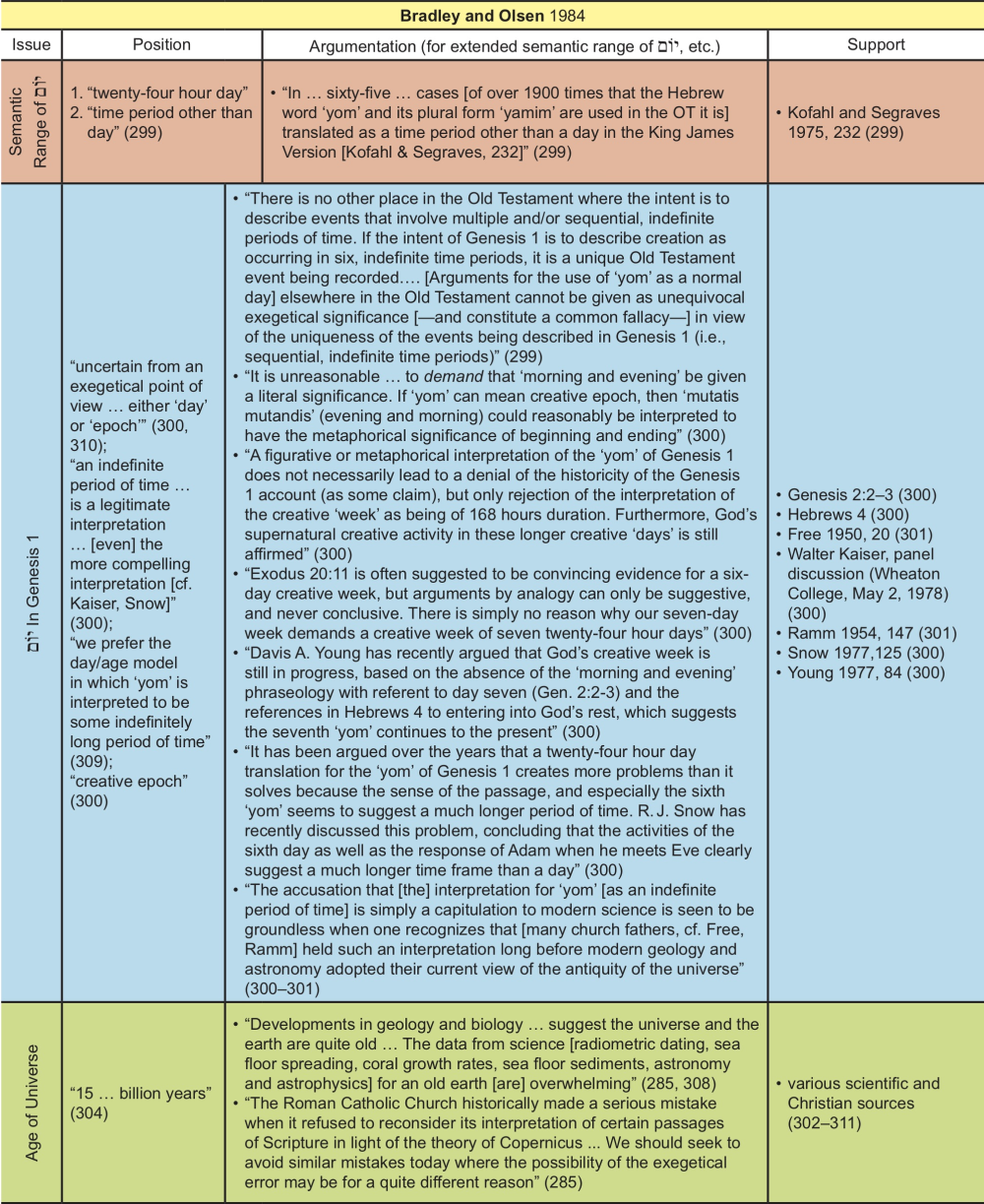

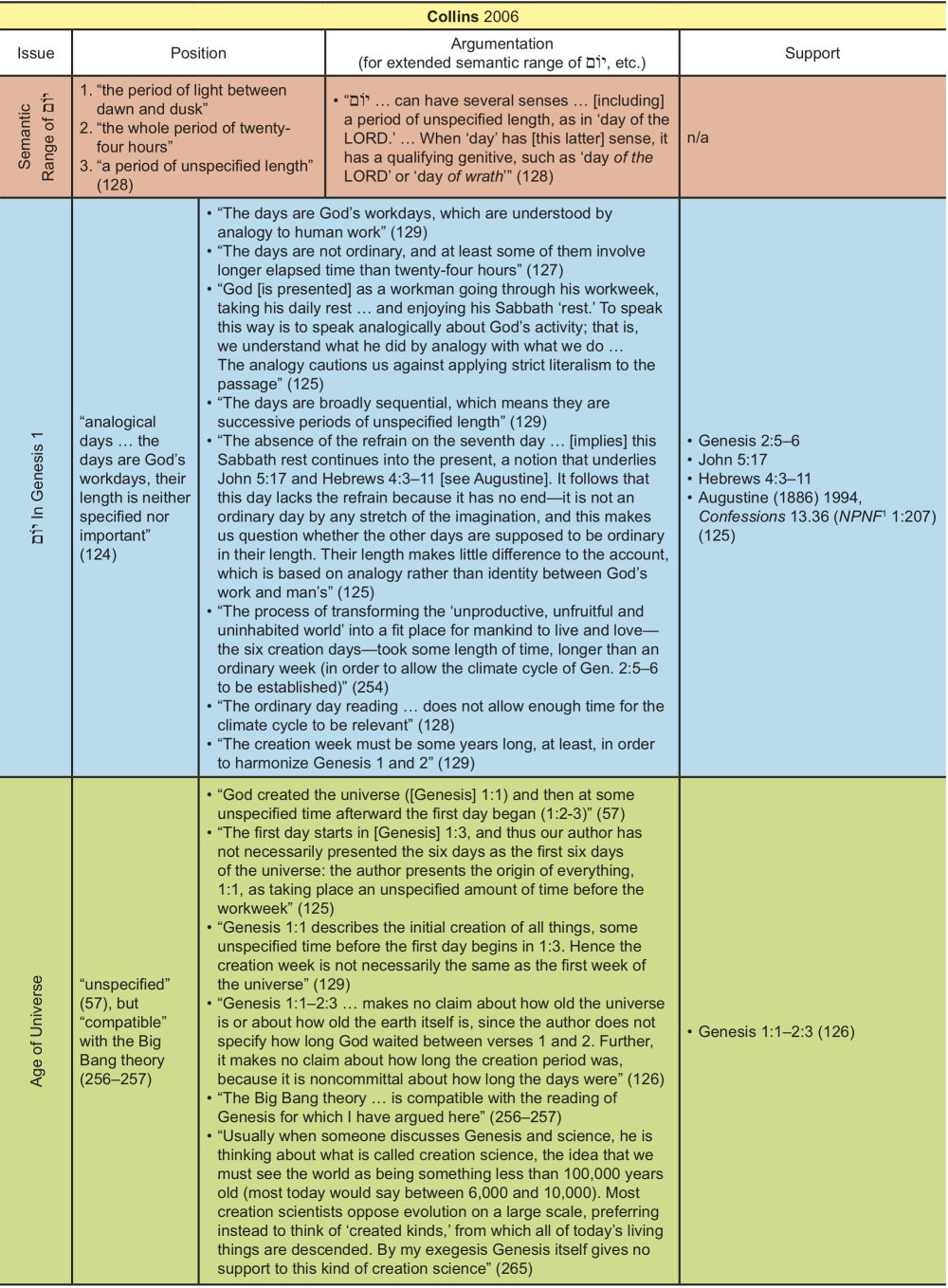

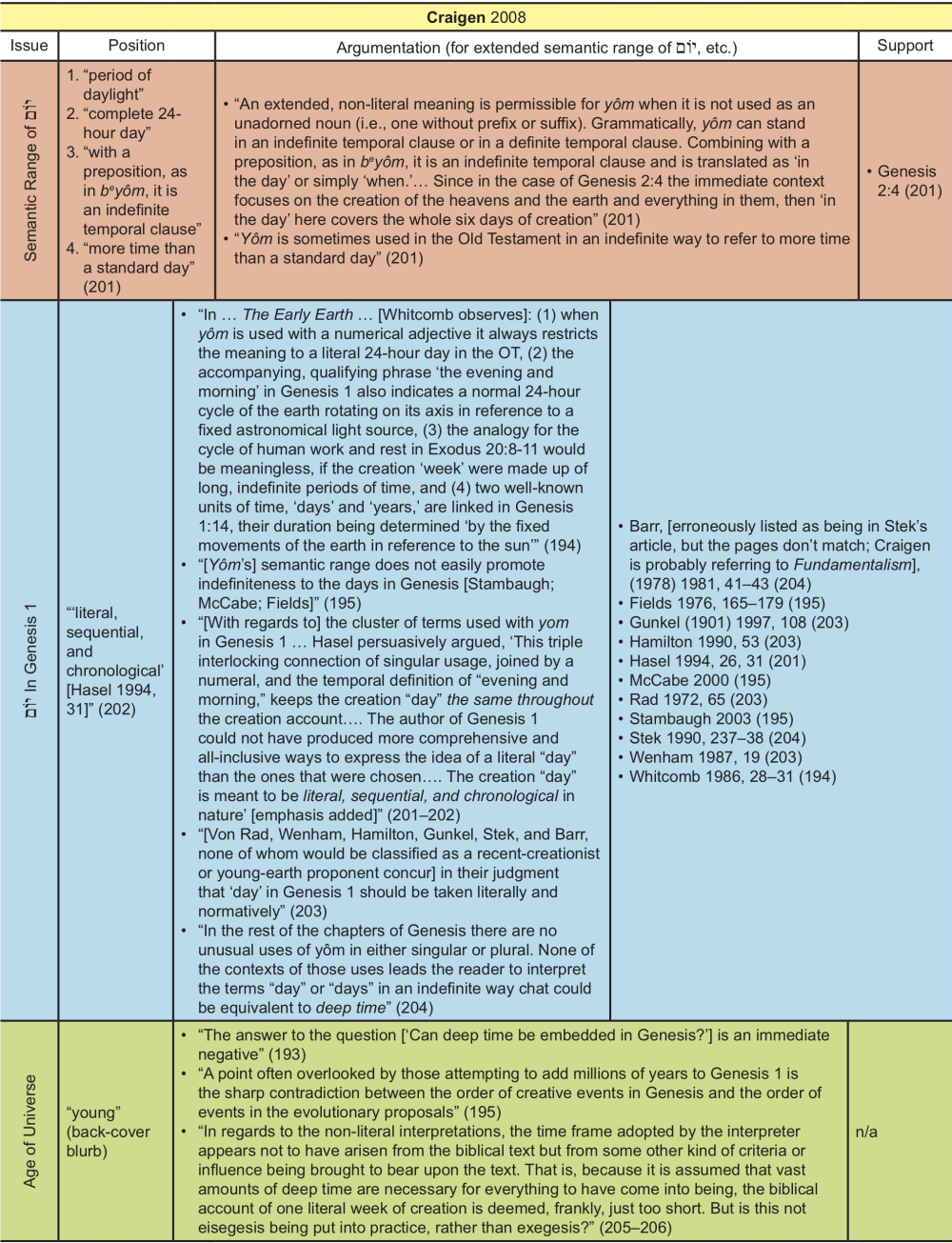

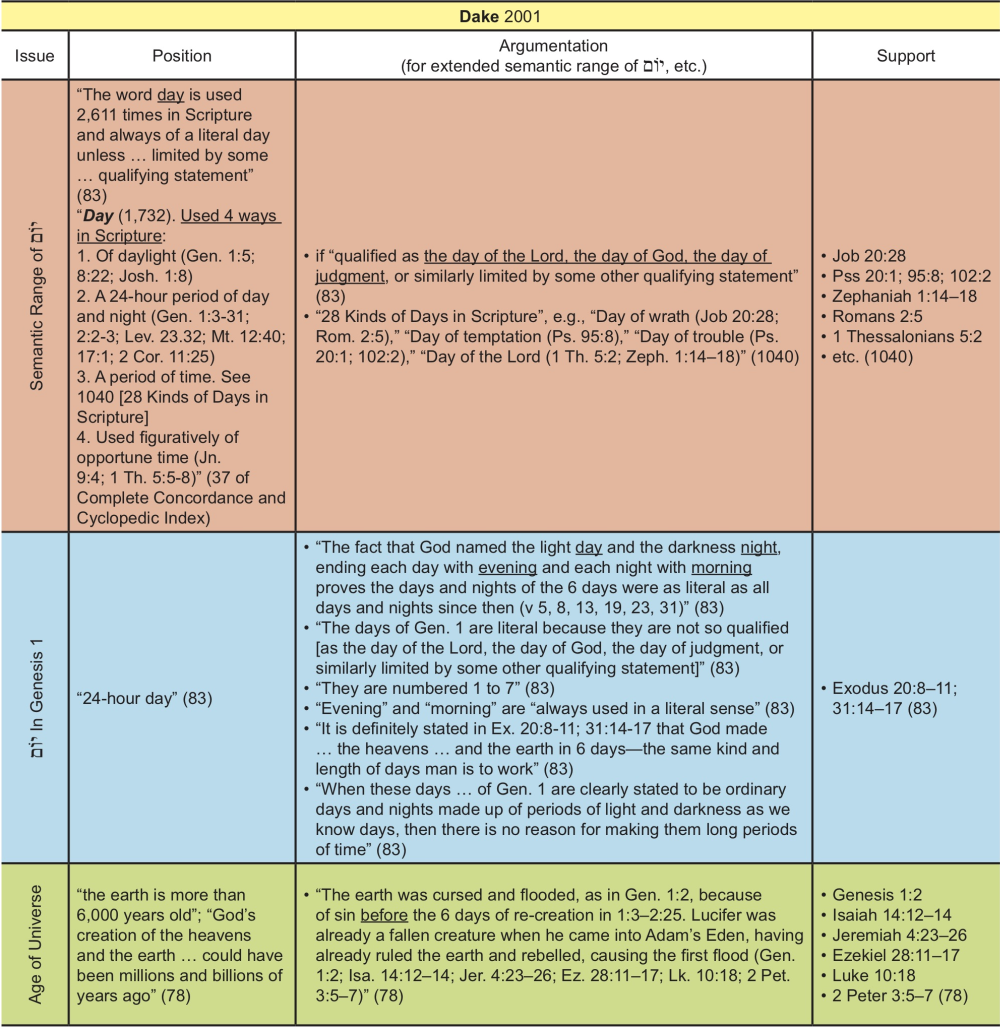

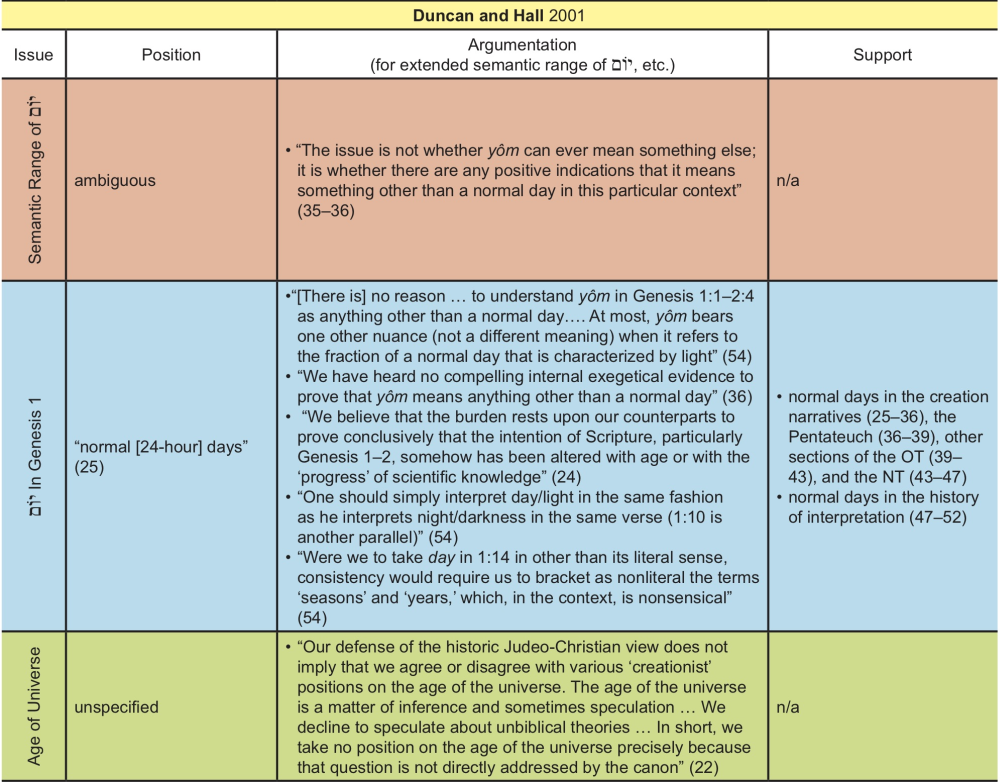

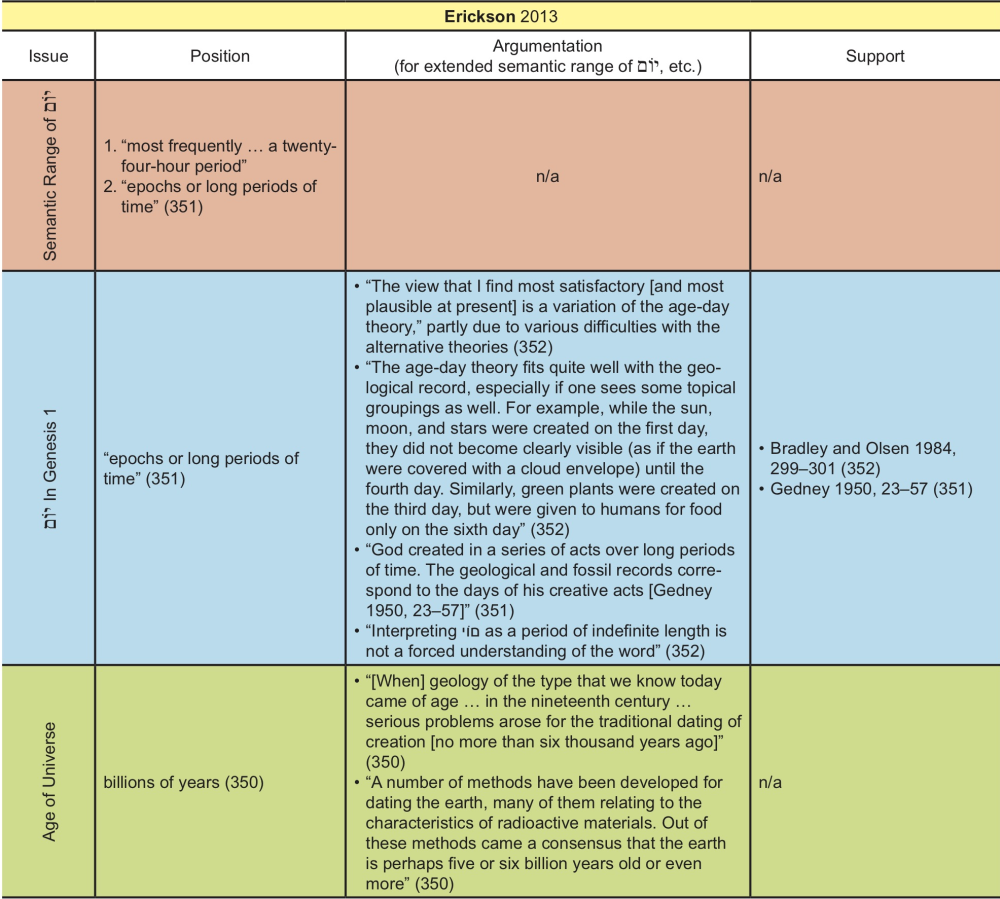

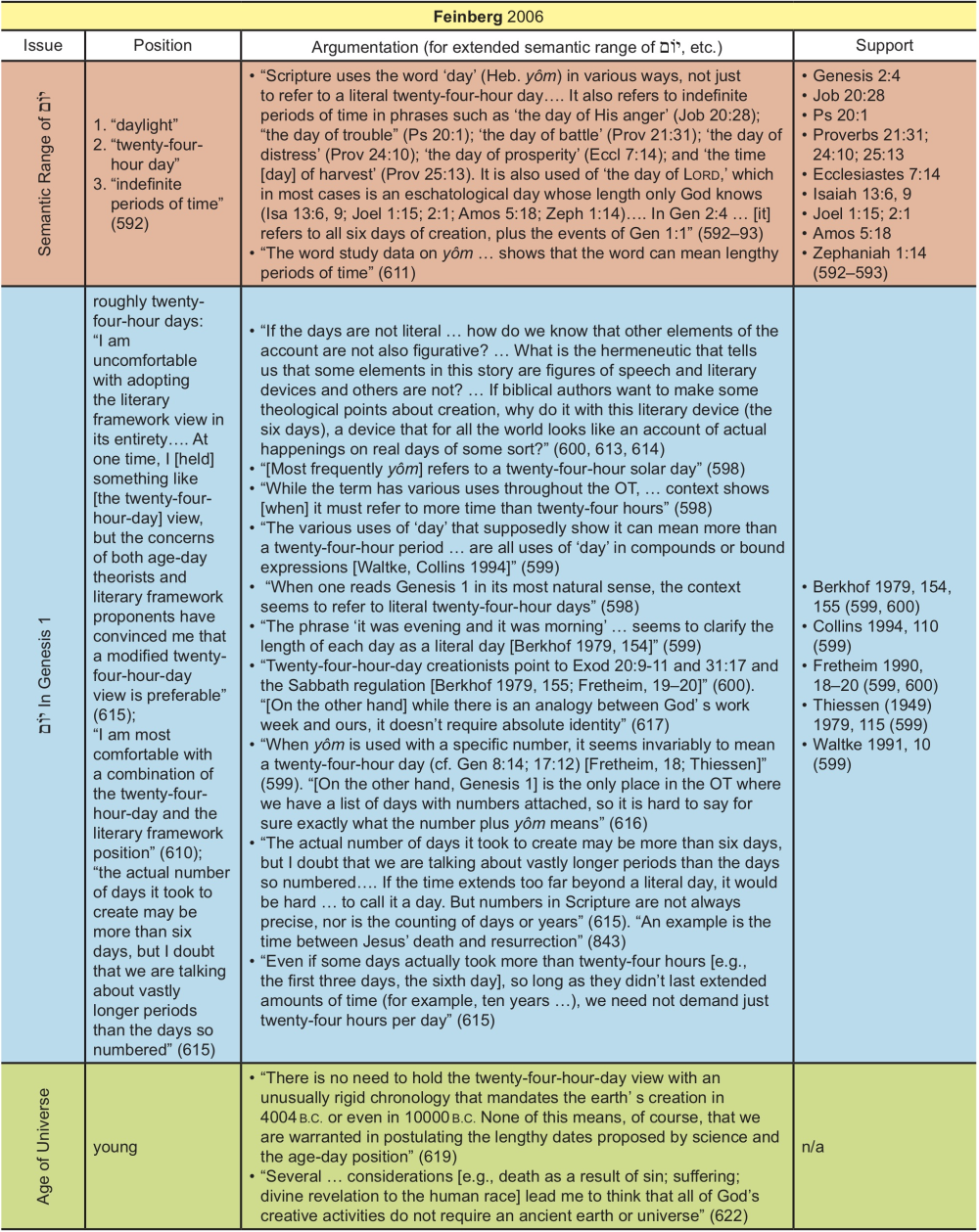

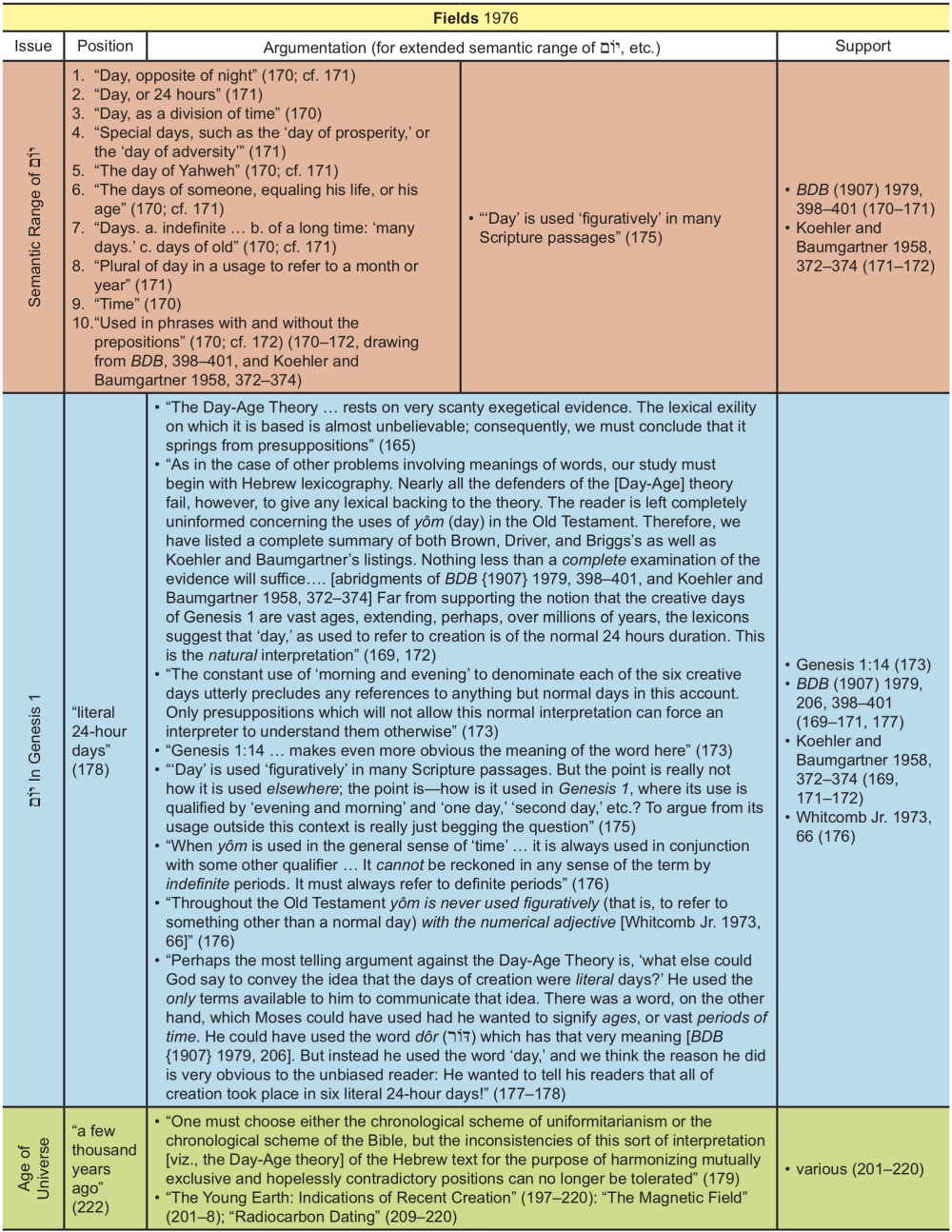

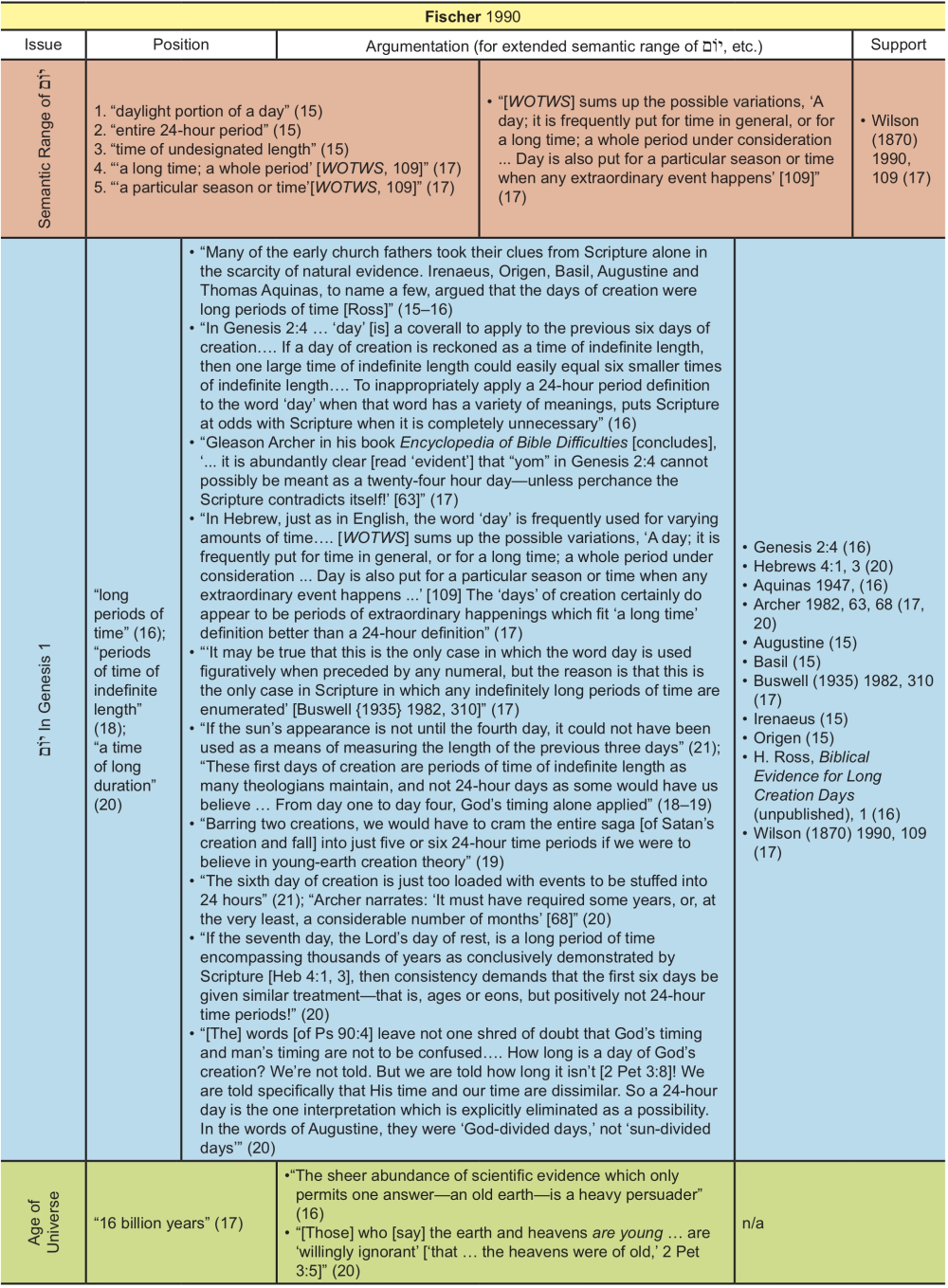

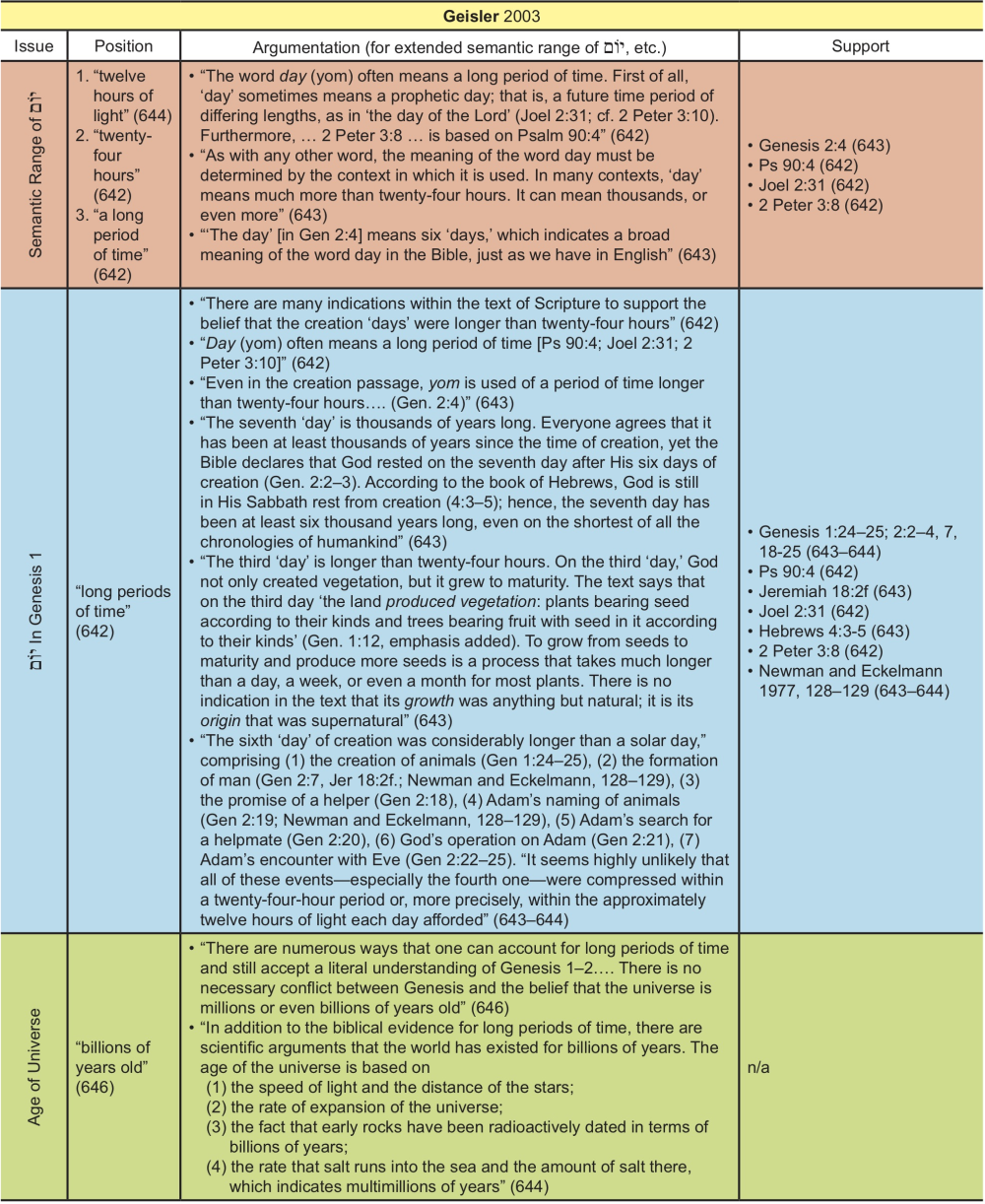

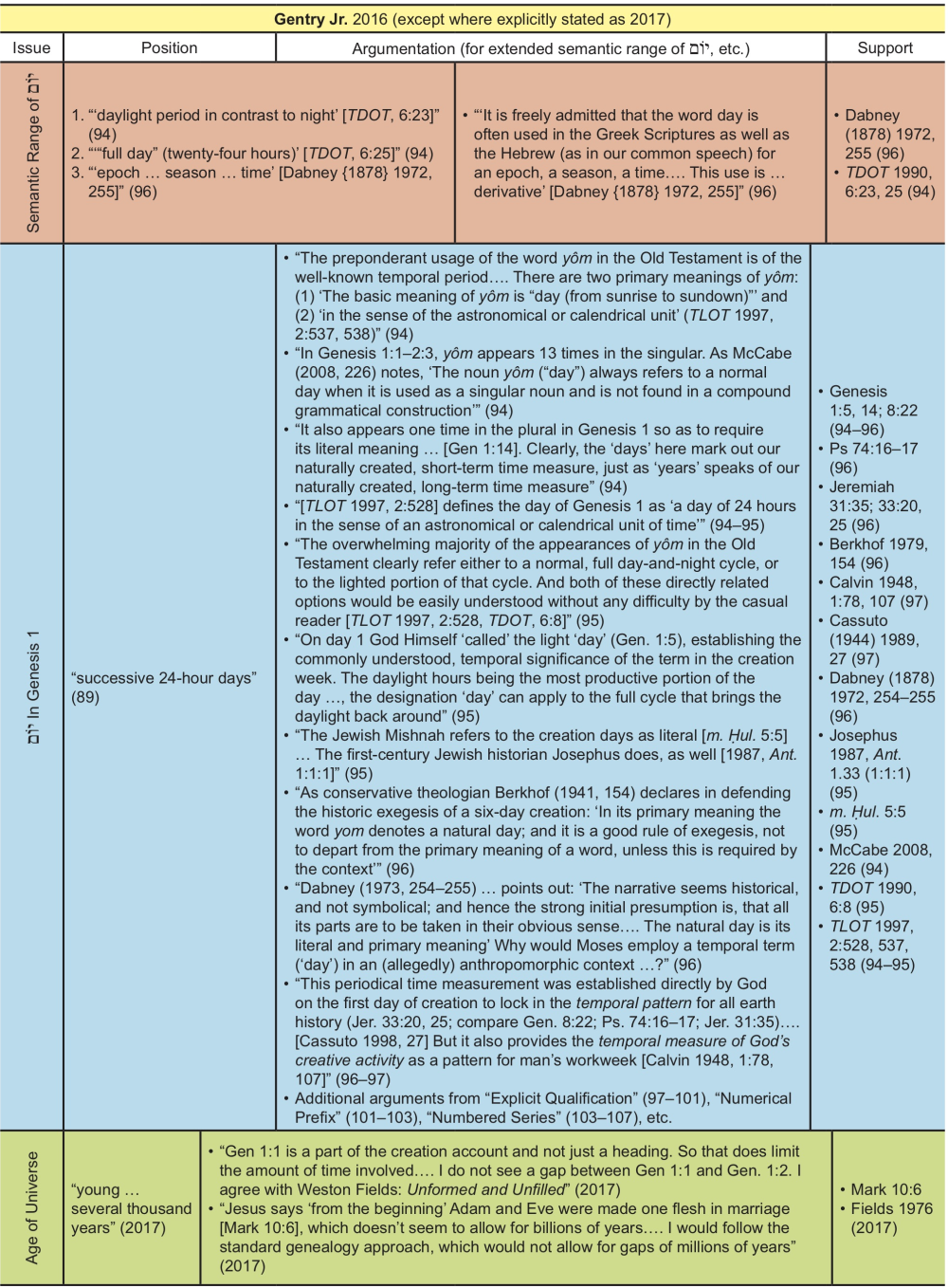

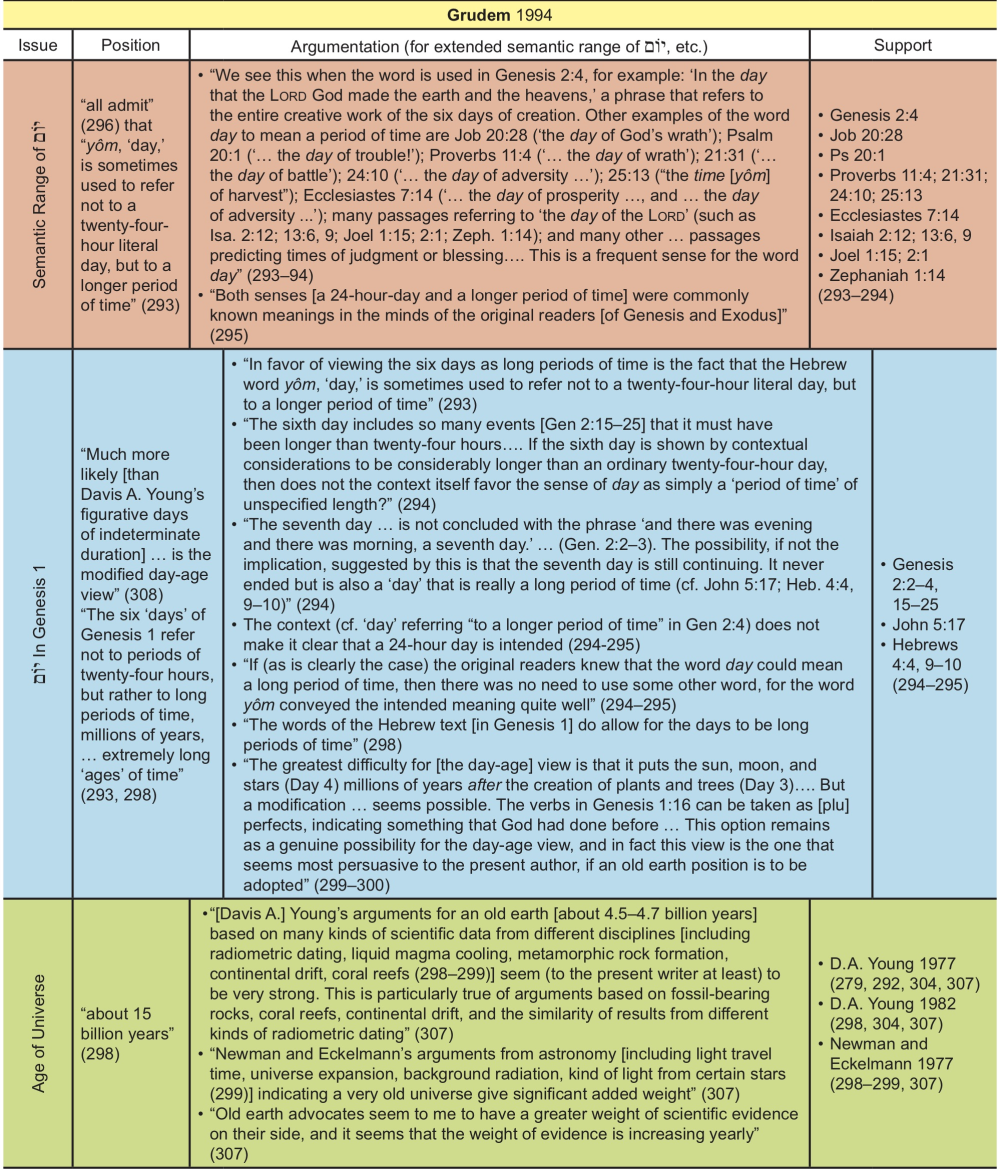

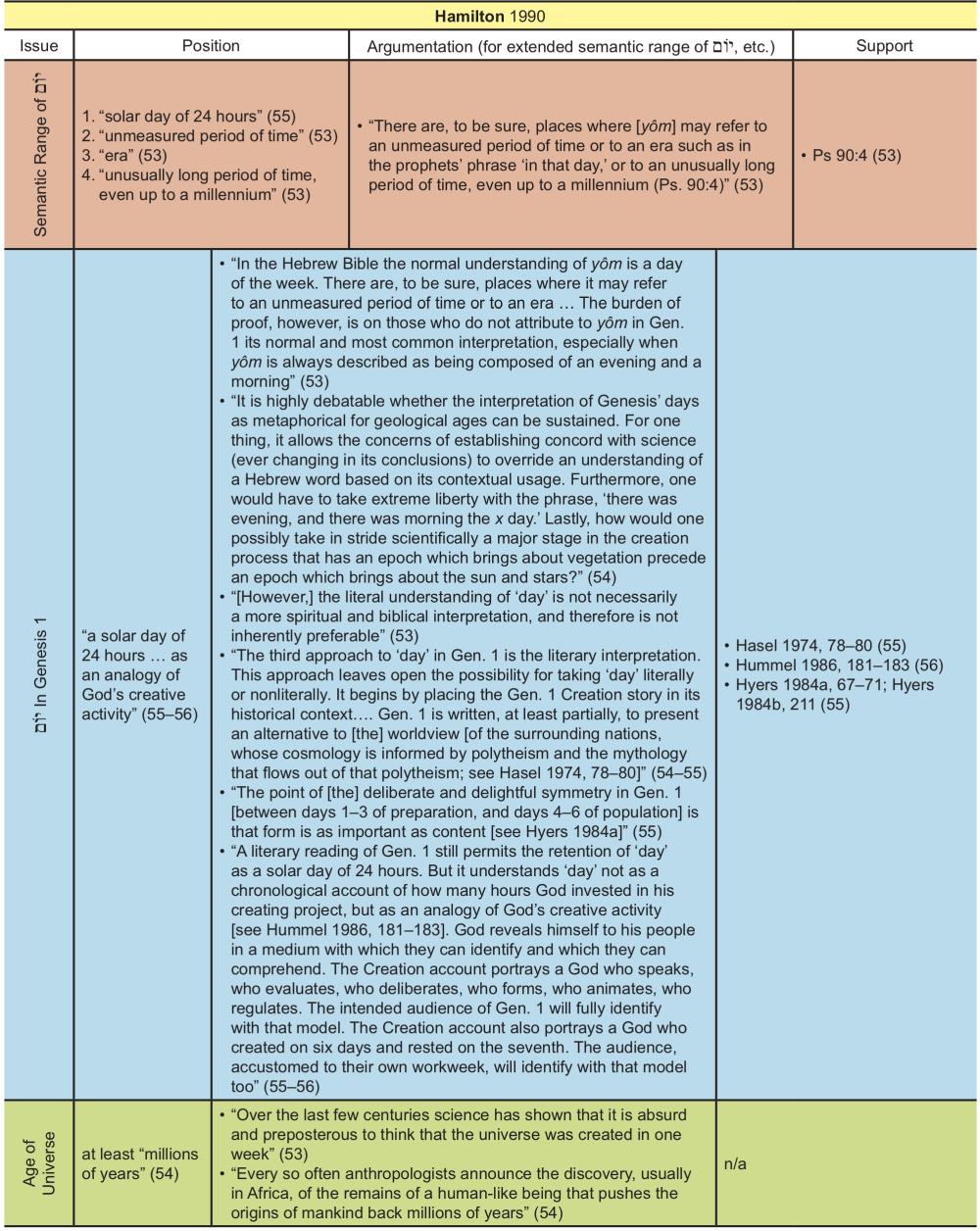

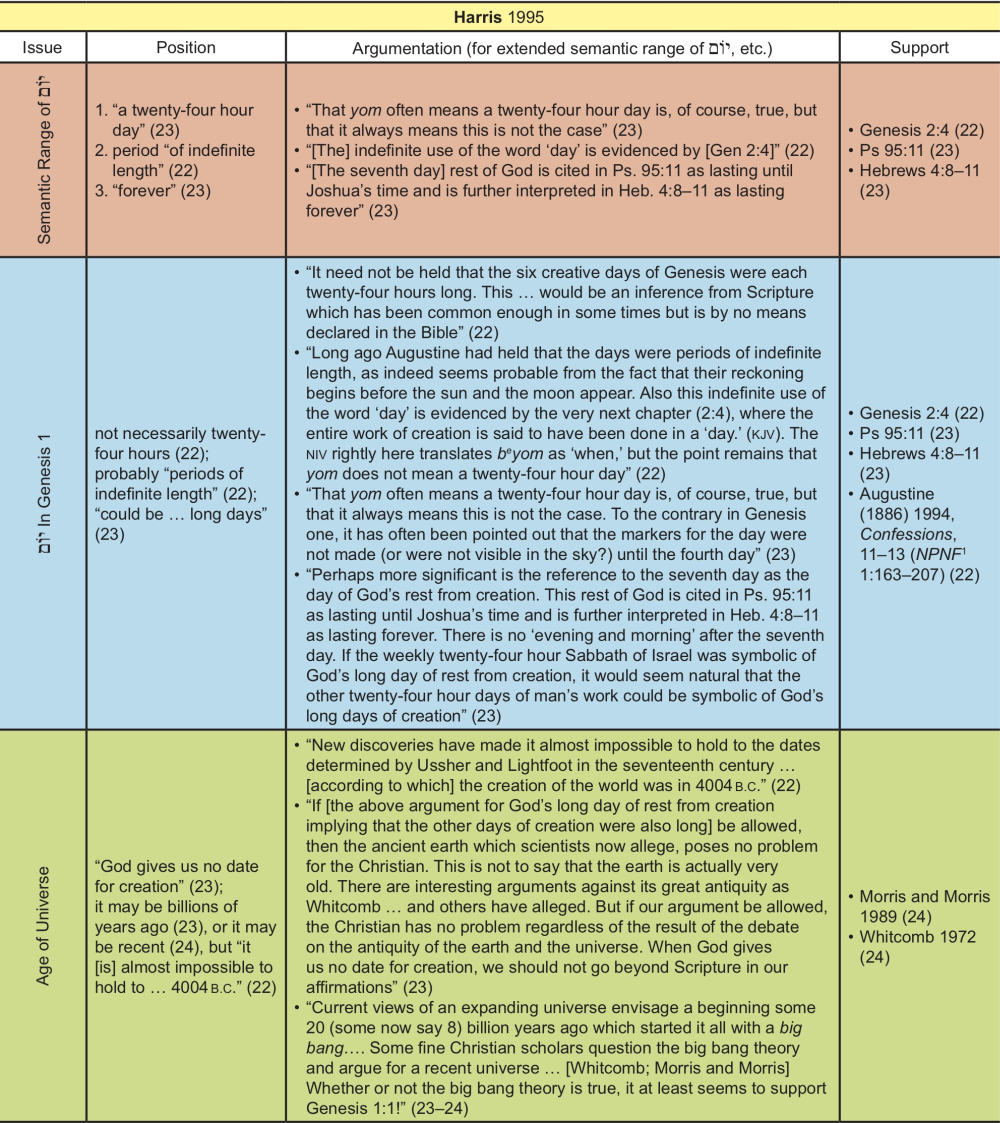

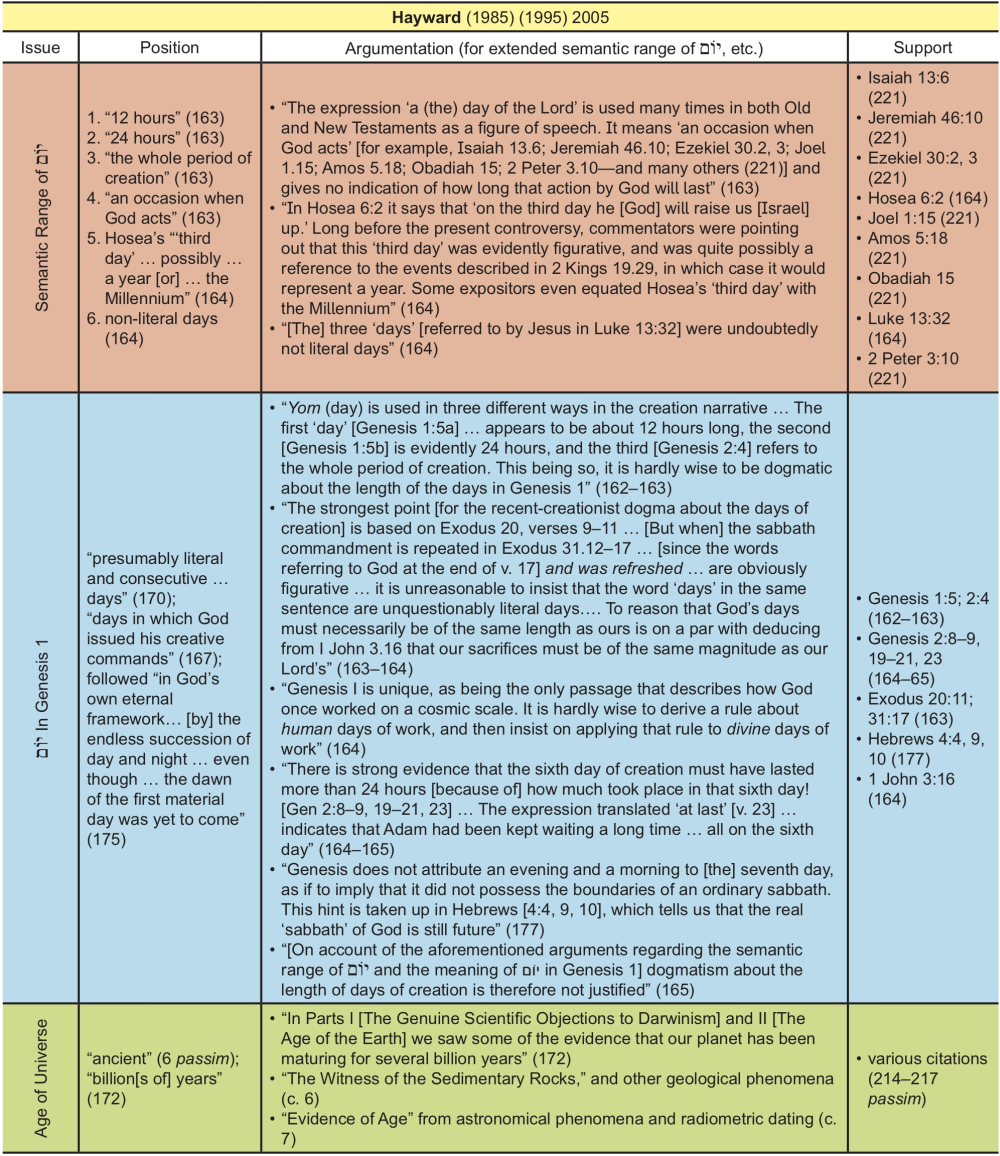

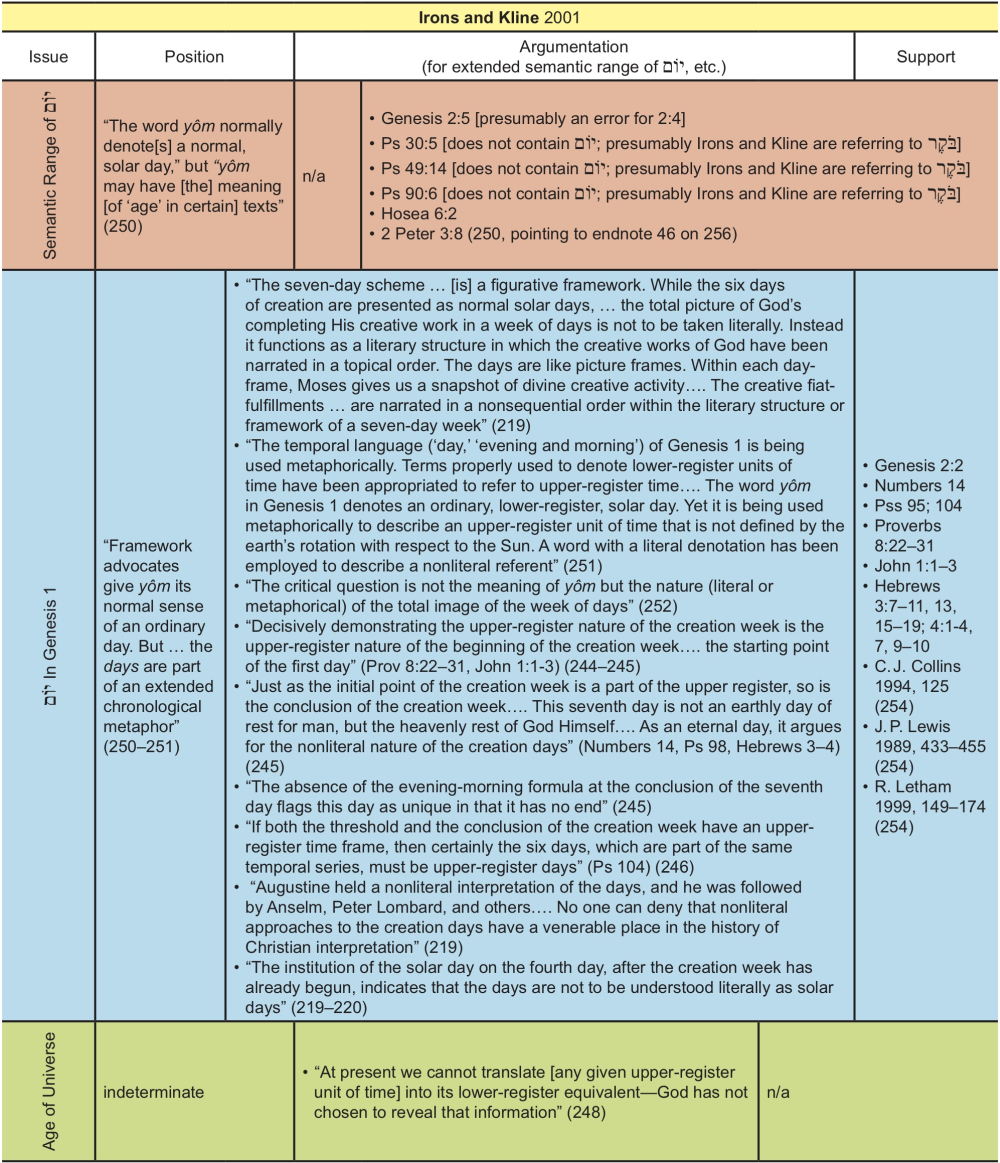

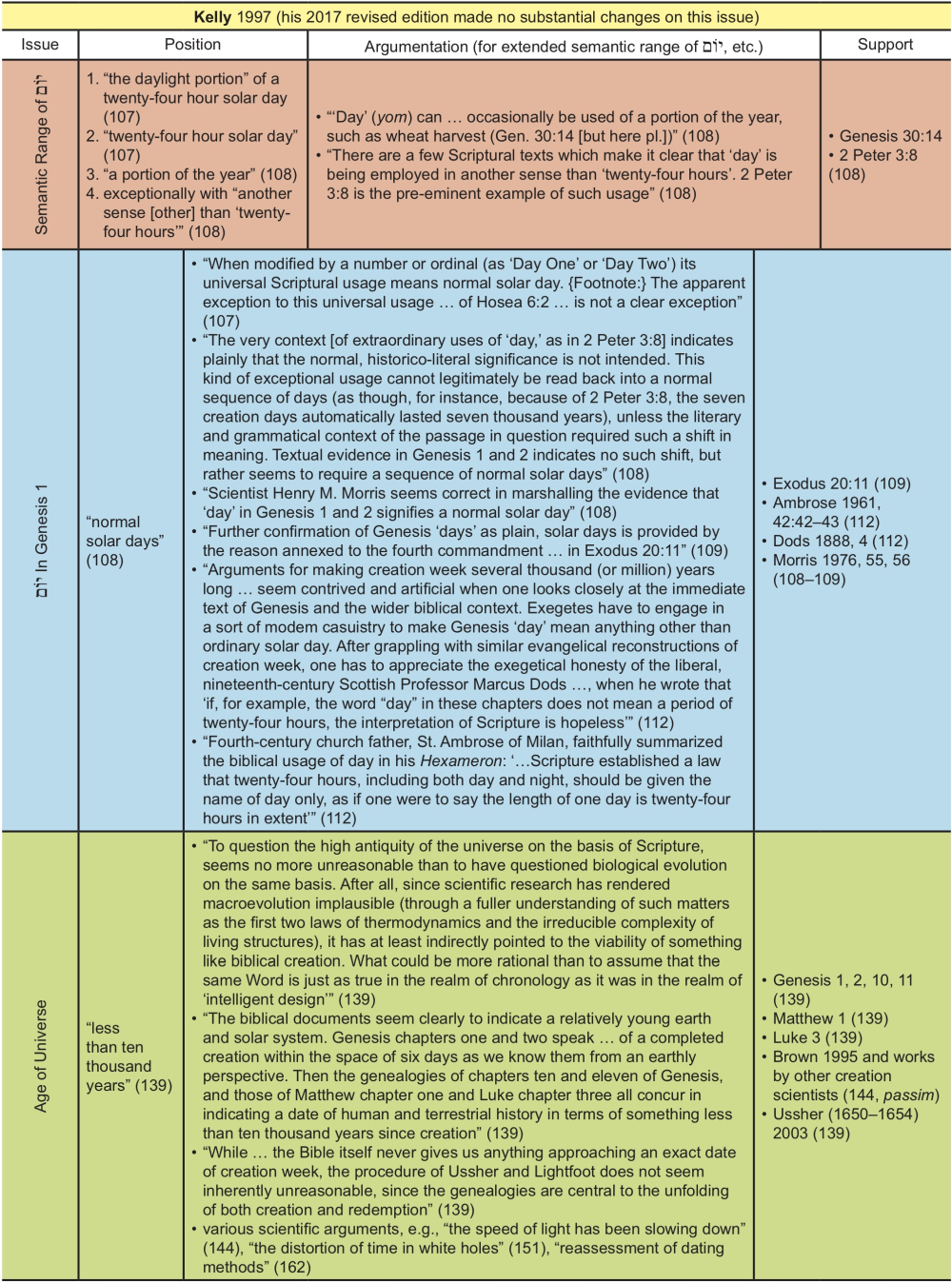

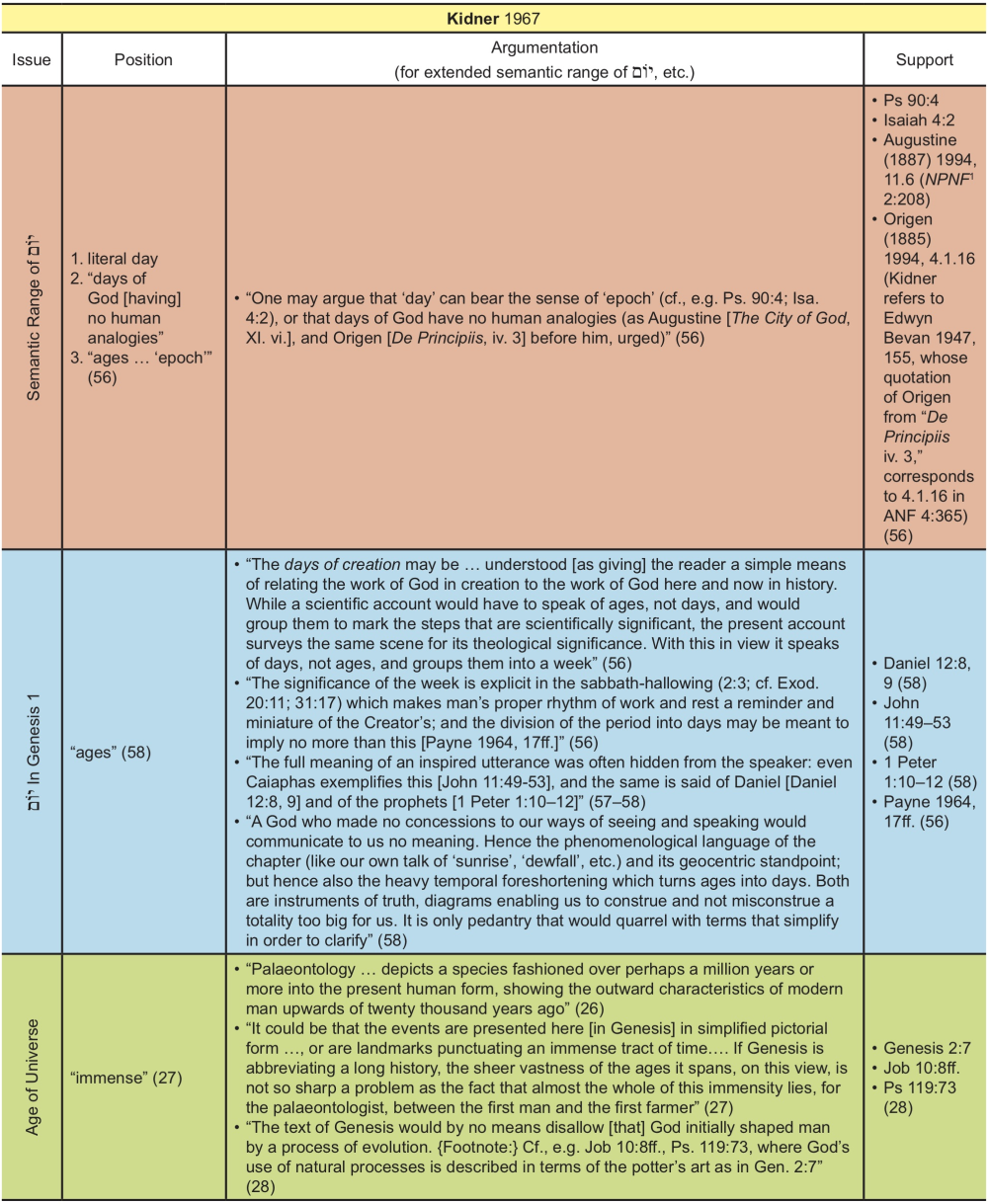

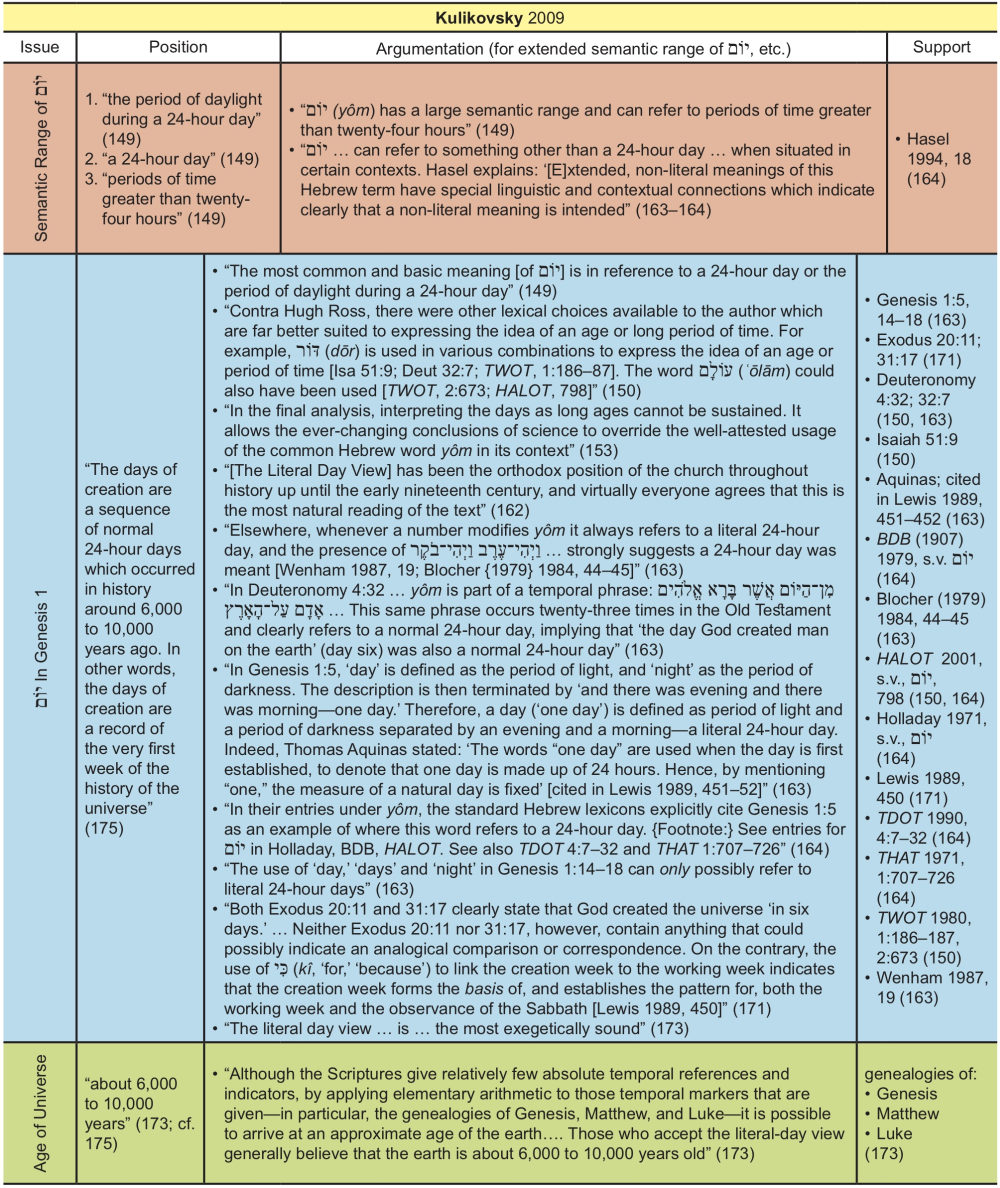

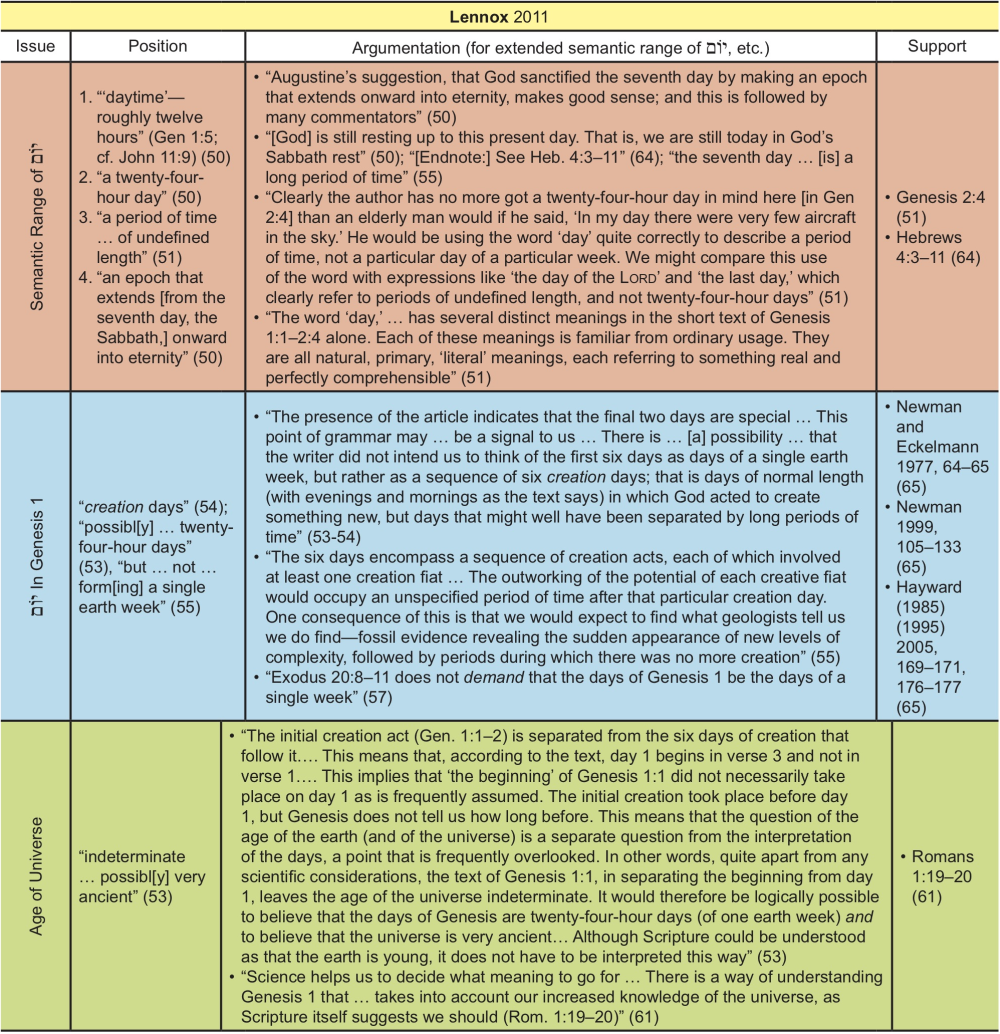

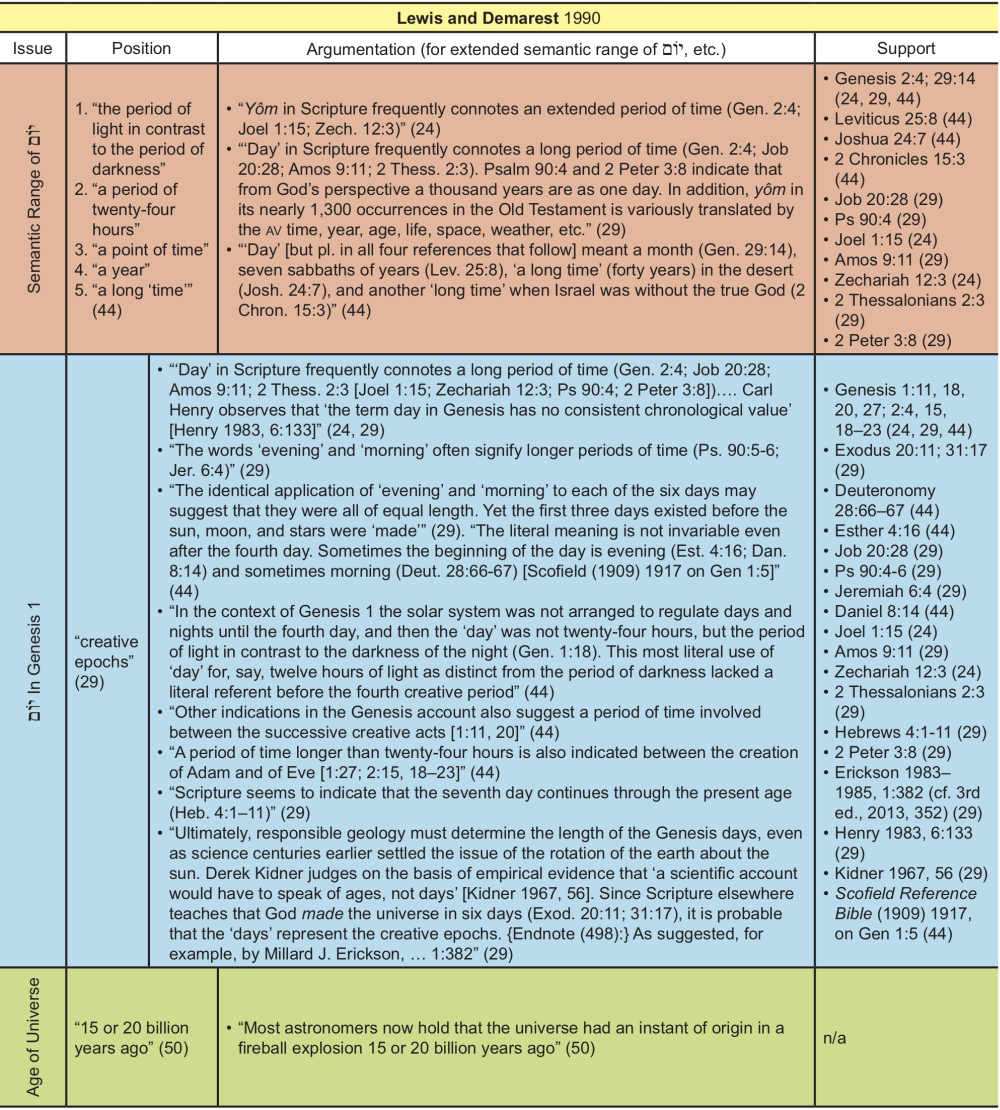

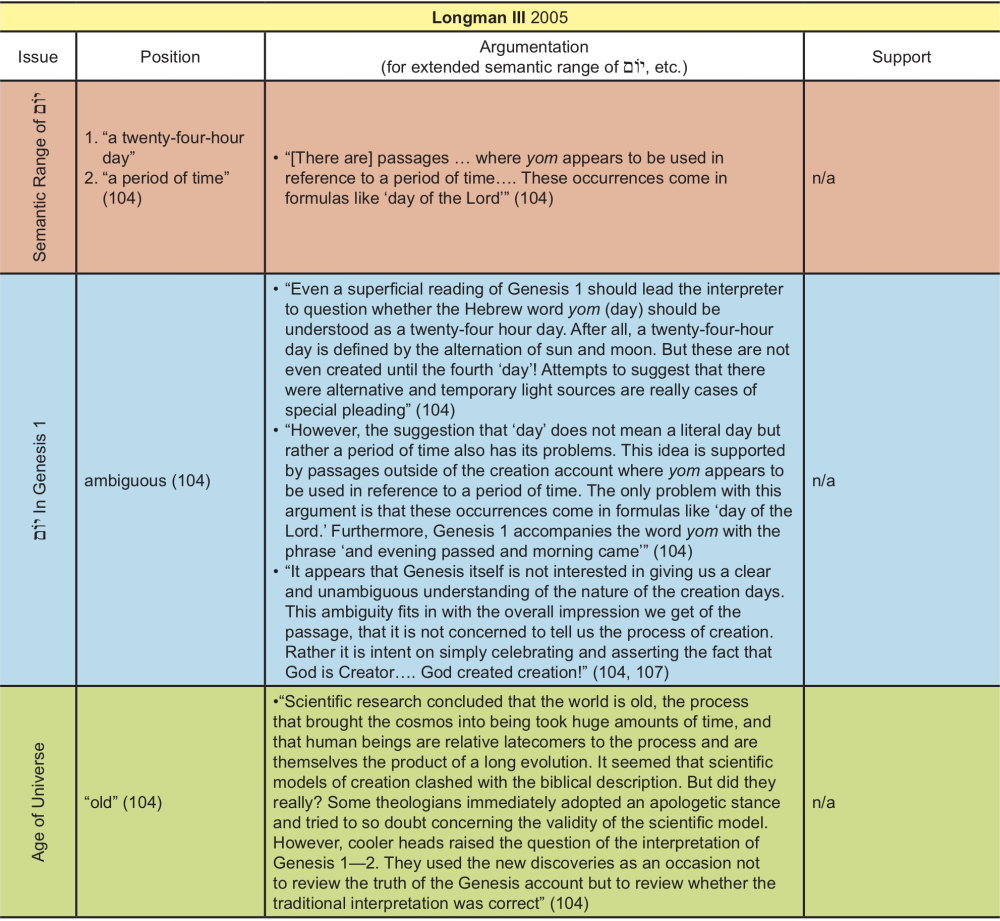

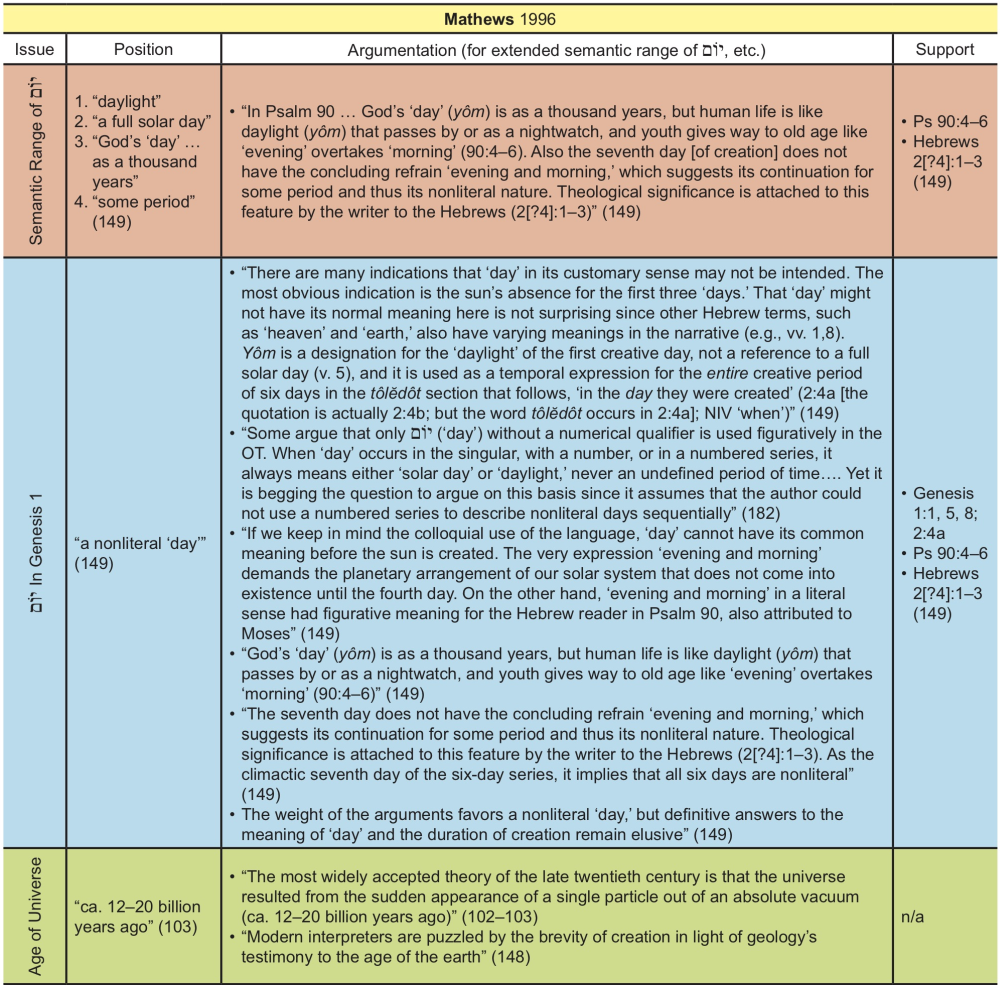

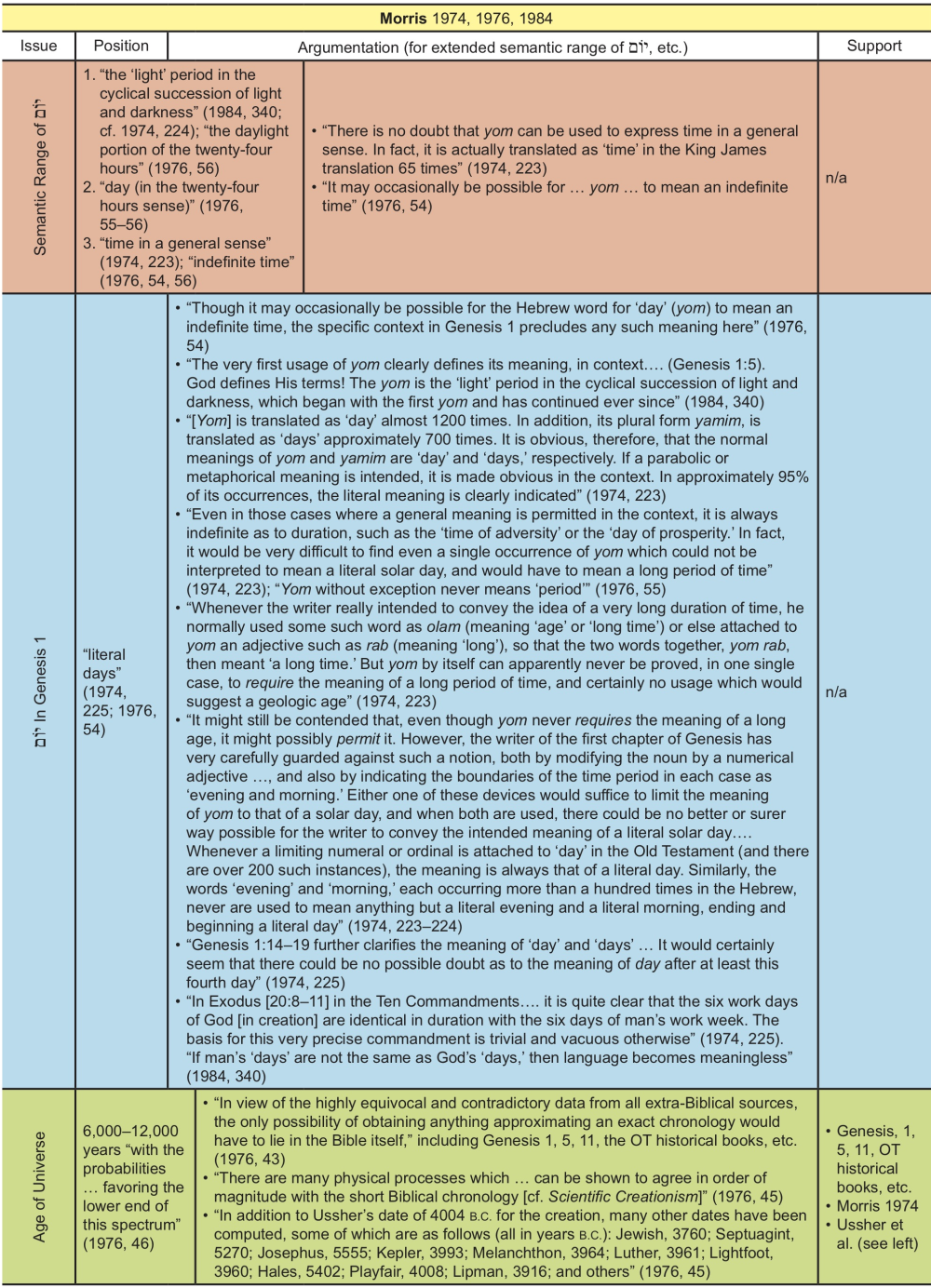

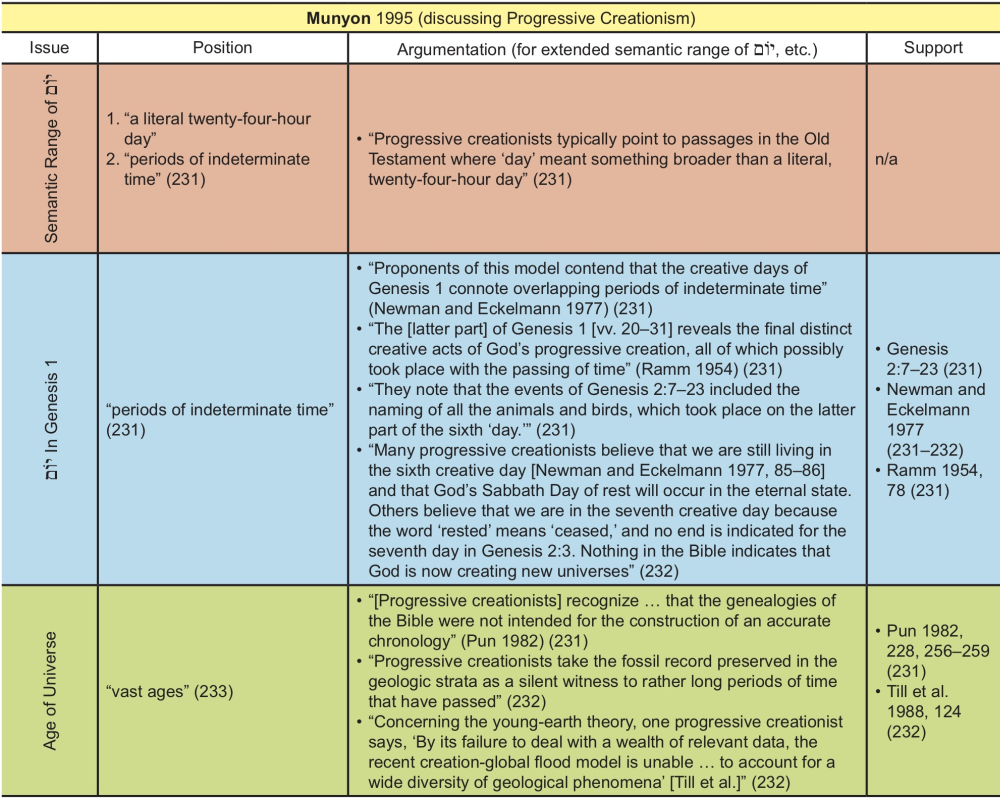

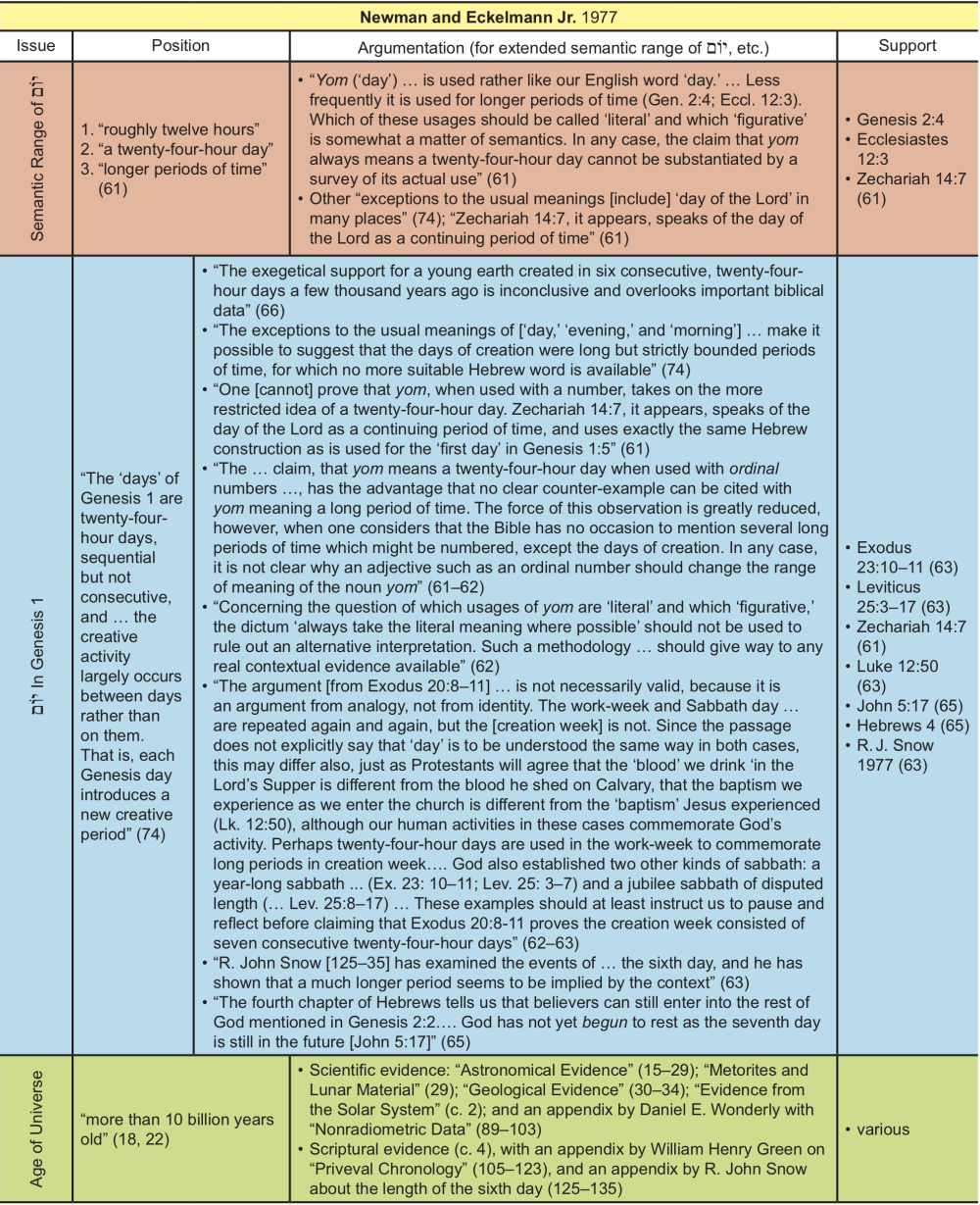

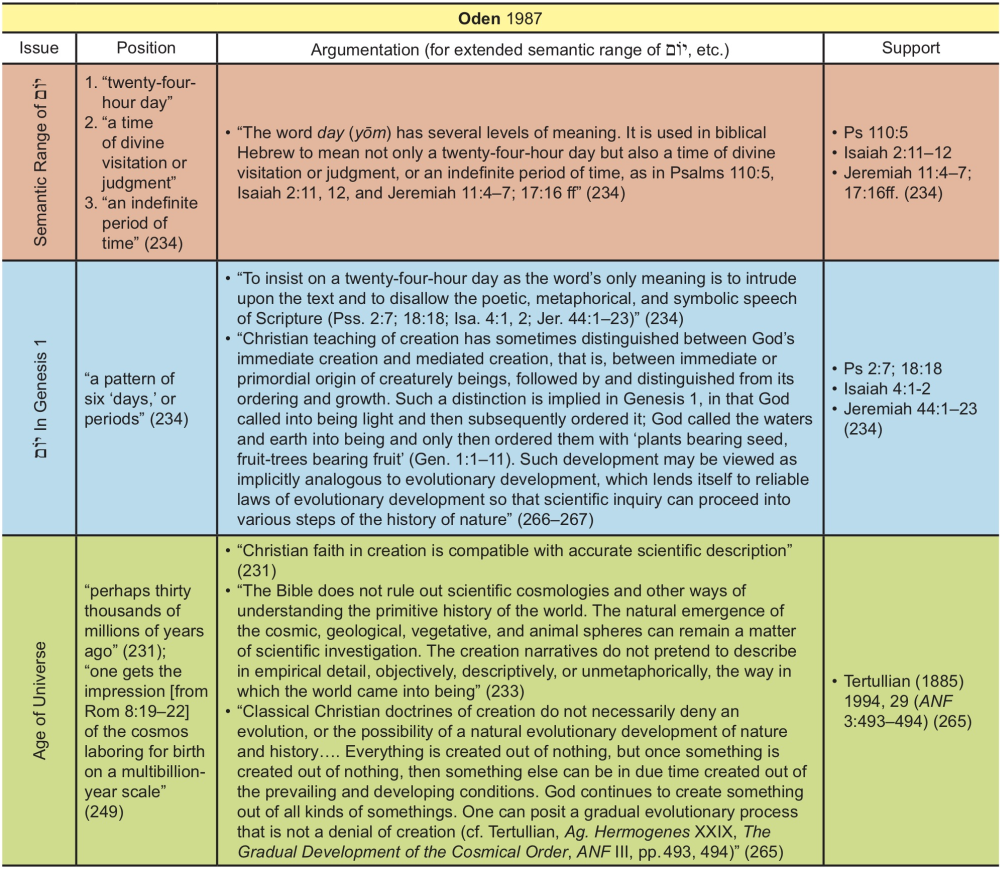

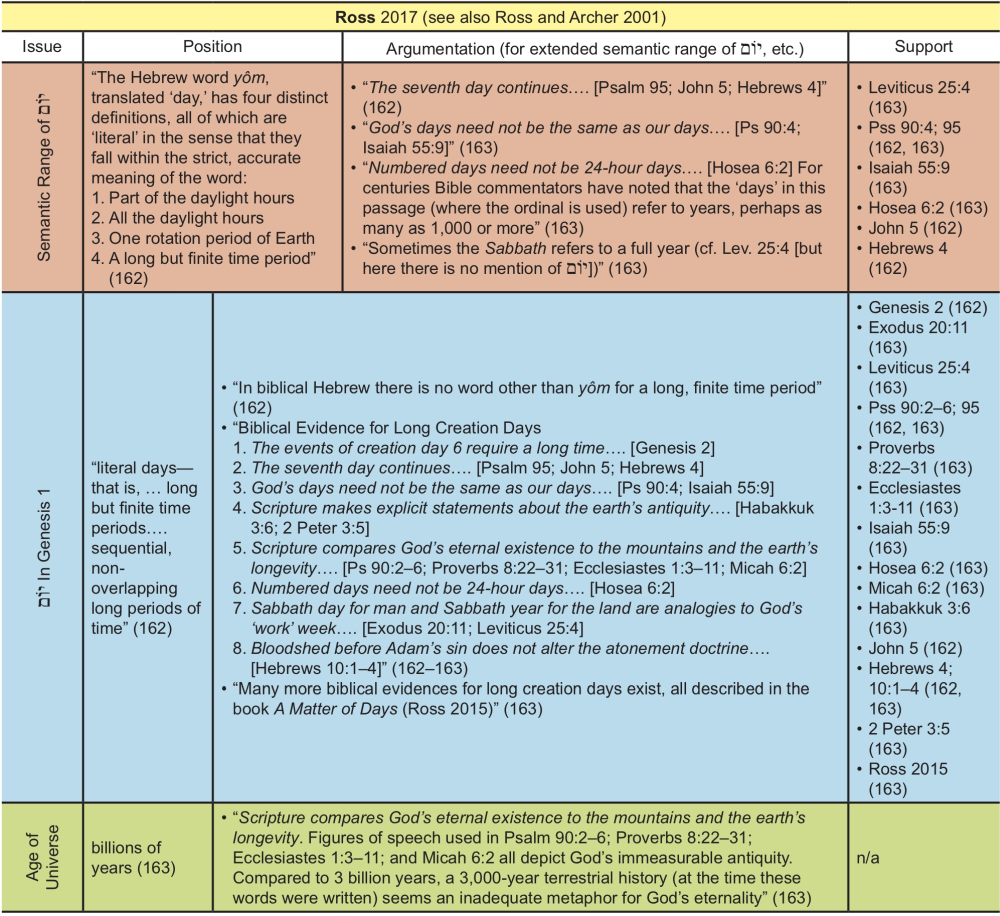

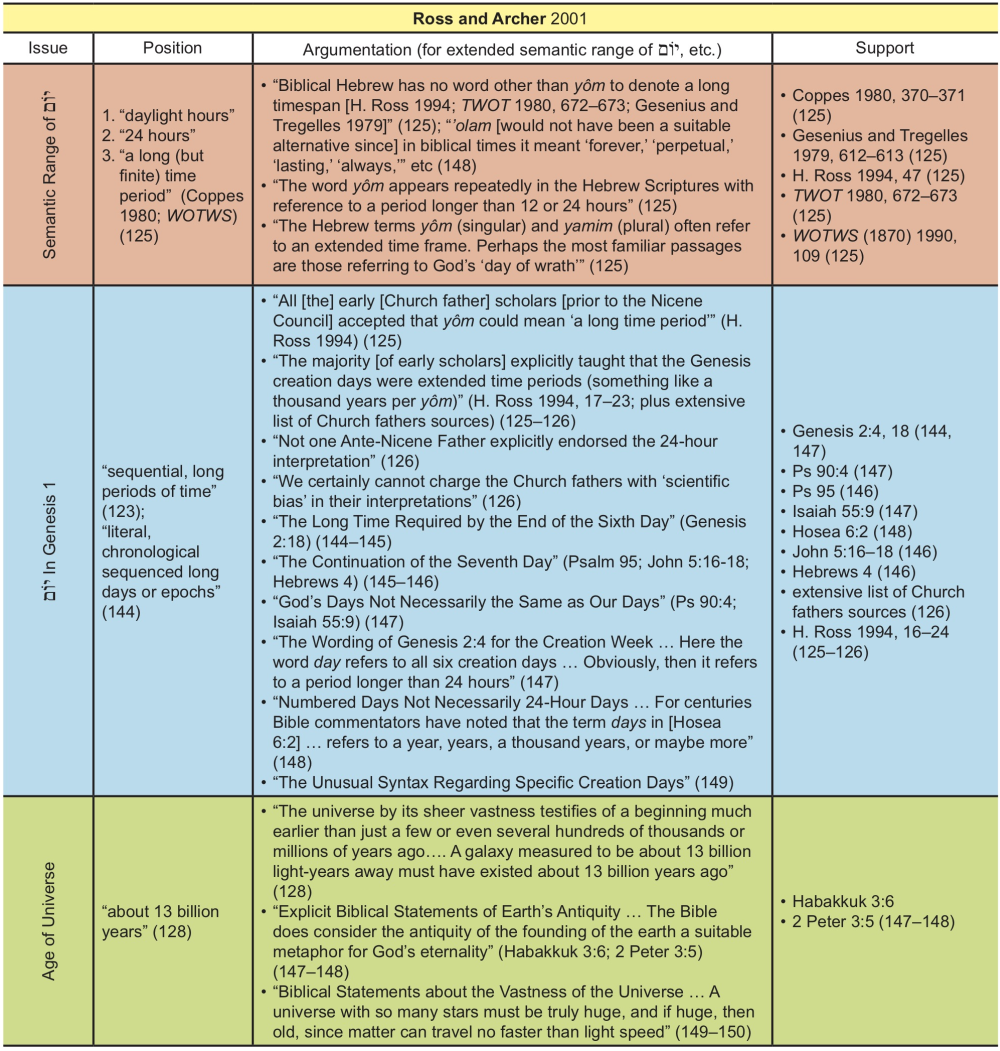

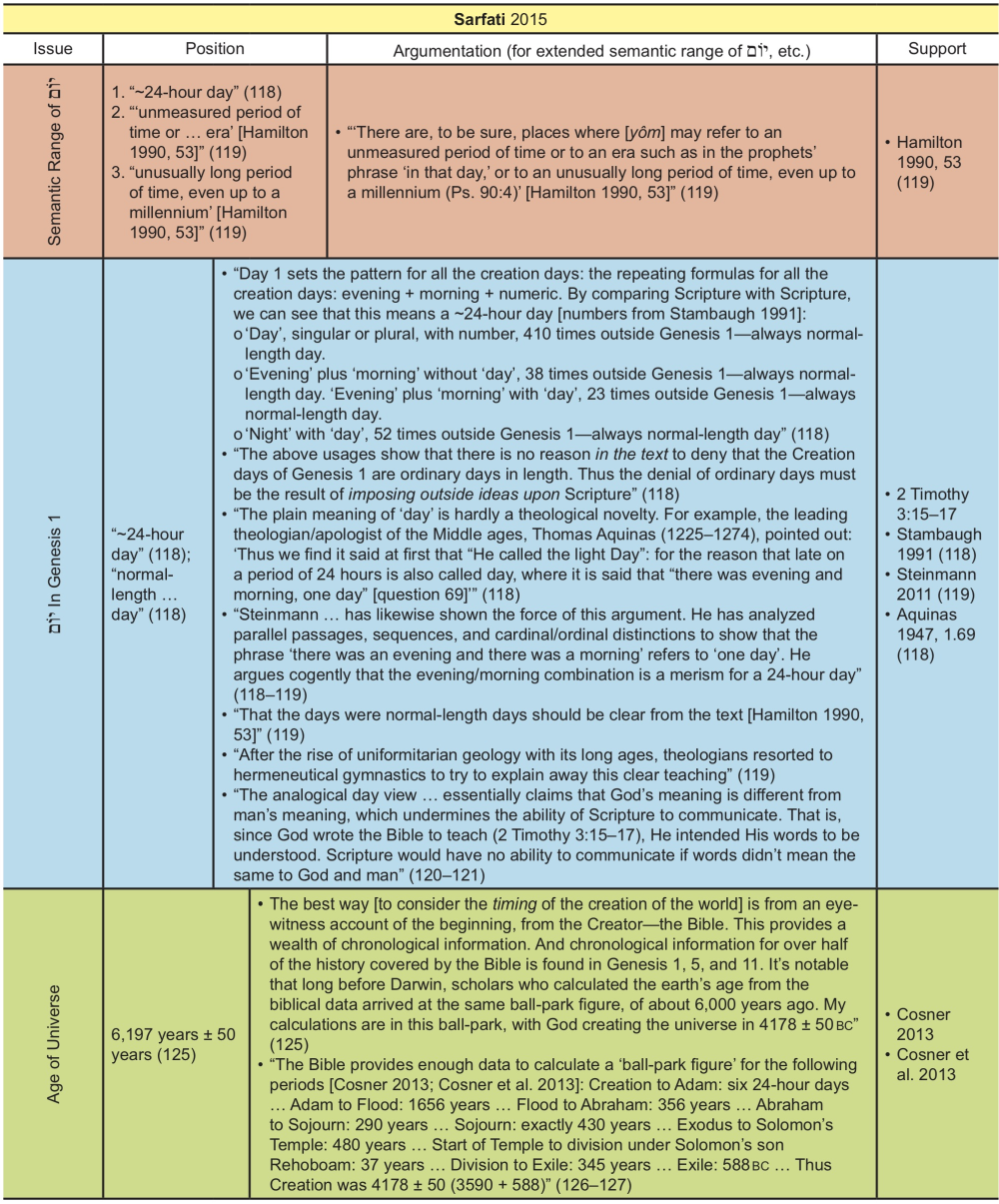

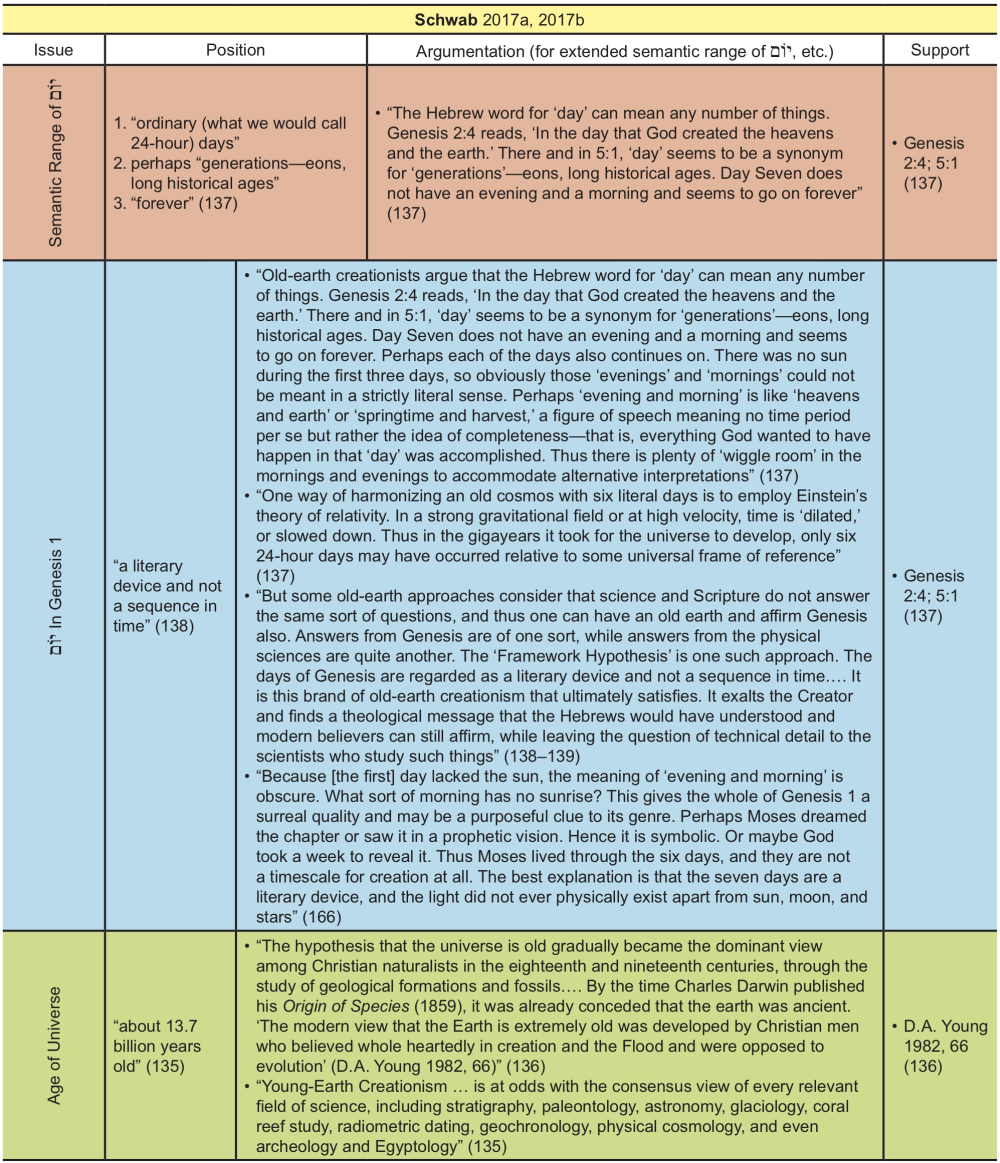

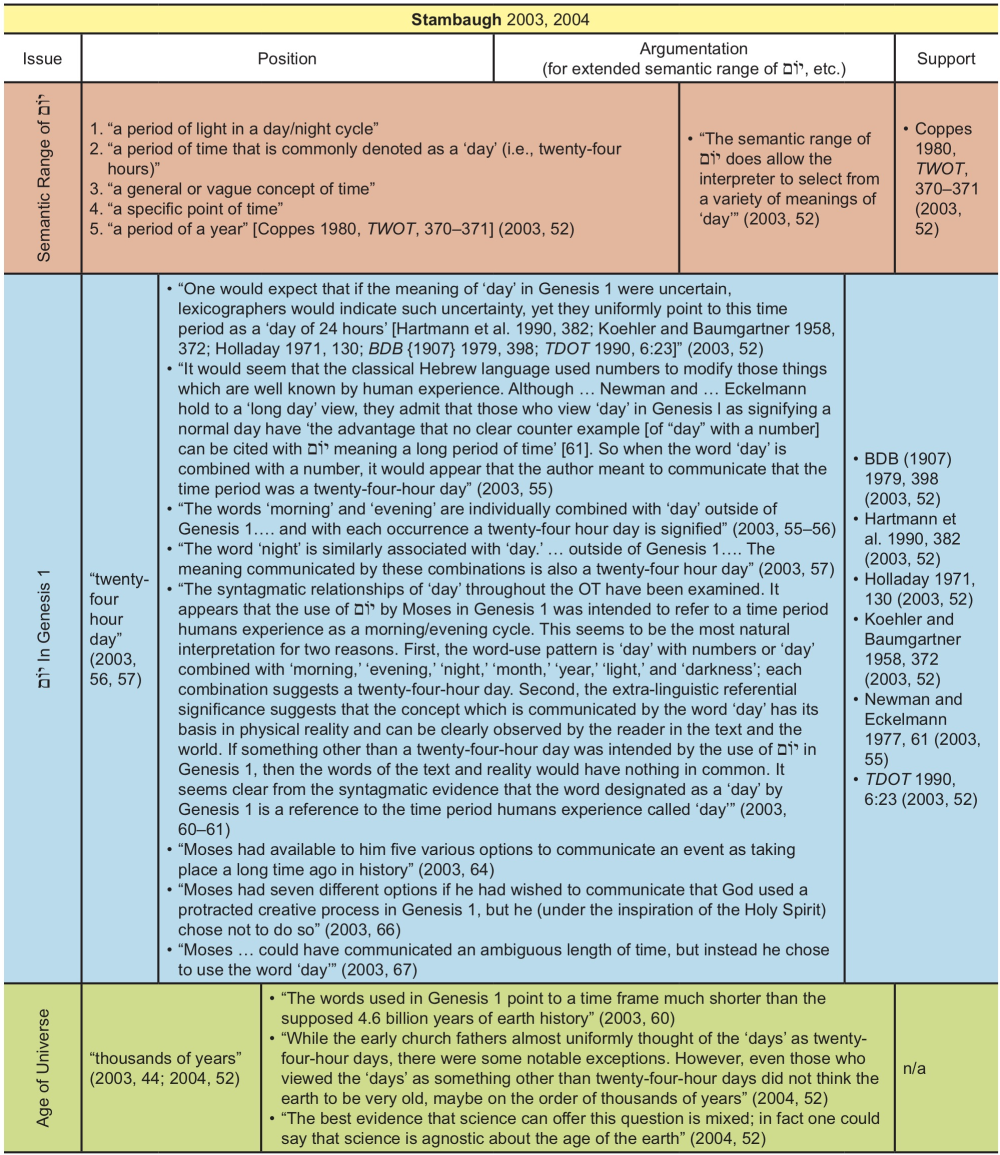

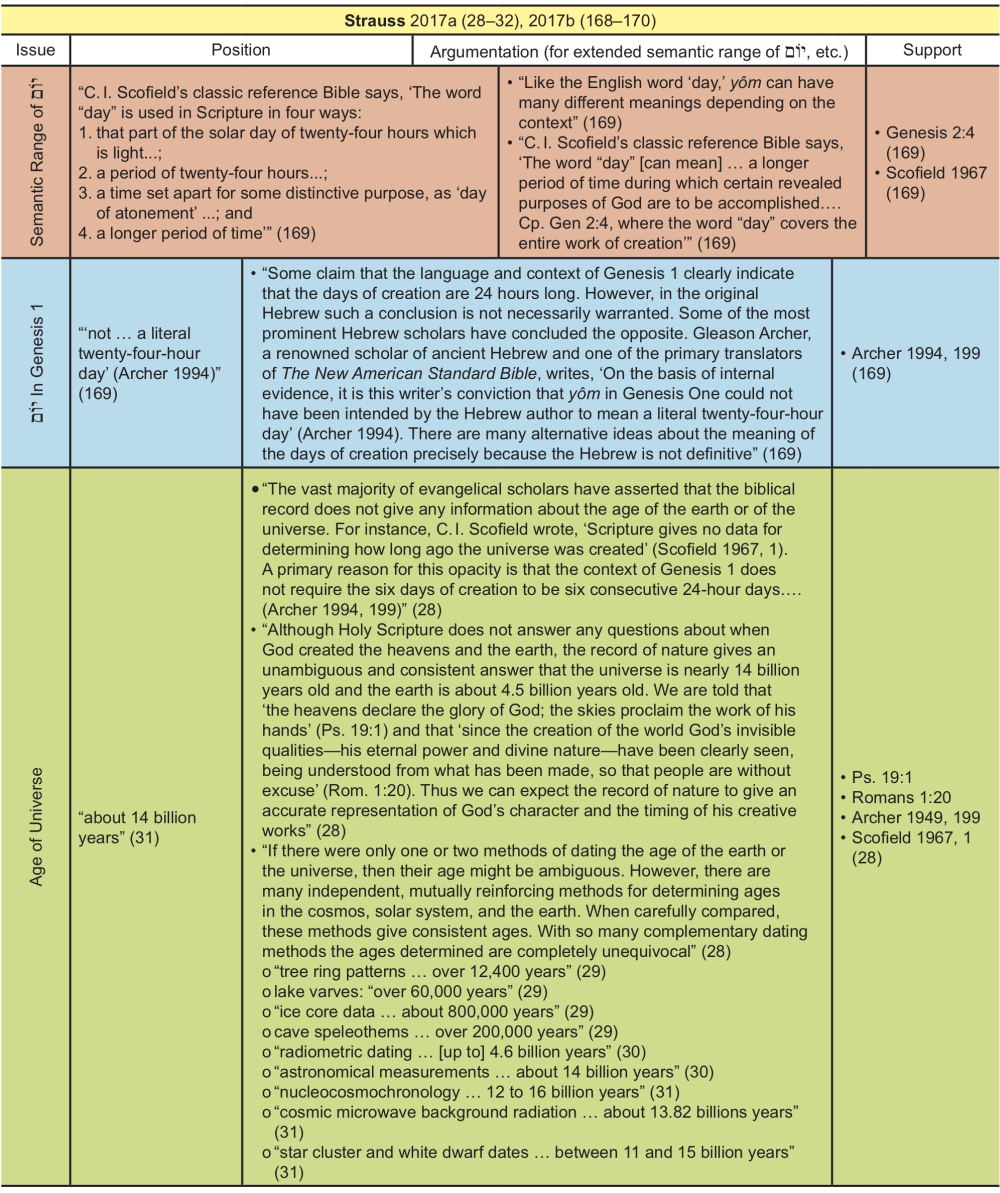

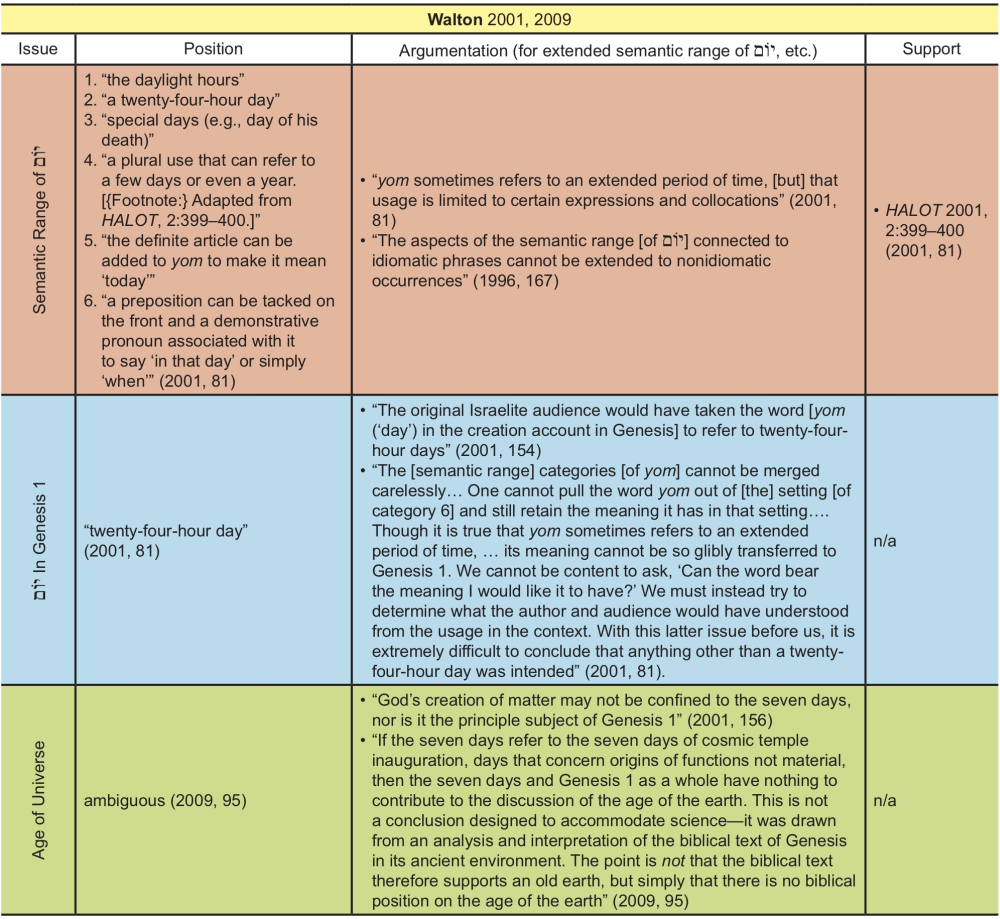

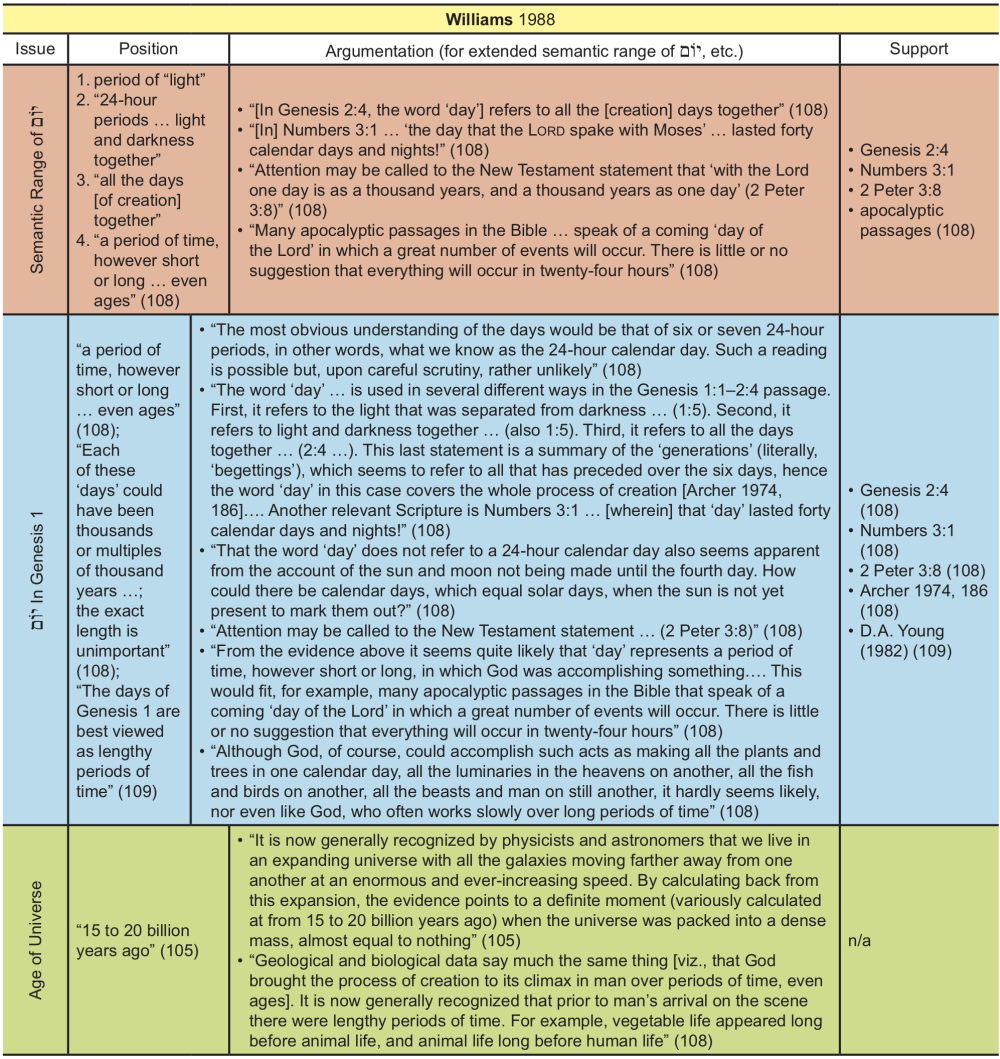

Appendix 1 is a compilation of the key points made by over forty scholars in their discussions of the days in the creation account, and of the age of the universe. The data are arranged such that the viewpoints of each scholar, or team of scholars, are contained on a single page in three rows. Each row presents, across three columns,

- the position advocated,

- the argumentation employed in favor of that position,

- references to any supporting evidence, whether Scriptural or scholarly.

The three rows cover the subjects of

- the semantic range of יוֹם,

- the meaning of יוֹם in Genesis 1,

- the age of the universe.

Brown (2014, 285) speaks for many scholars when he observes that, from the time of the early church fathers right up to the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, “Non-literal interpretations of the days of Genesis formed a … minority strand.” Even in the modern era, with the growth of interest in alternative interpretations, such as the Day-Age Theory, there has been a consistent voice, from both conservatives and liberals, in support of the traditional literal reading. Furthermore, the literal sense of a term is, by definition, its usual or most basic sense. For these reasons, since the burden of proof lies with advocates of non-literal interpretations, the following analysis of data will focus primarily on argumentation given in support of such a stance.

Extended Definitions of יוֹם, and Lines of Argument in Support of an Extended Semantic Range of יוֹם

Archer (1984, 327) observes, “All biblical scholars admit that yōm (‘day’) may be used in a figurative or symbolic manner, as well as in a literal sense.” Beyond the basic meaning of יוֹם as the daylight period in the daytime-nighttime cycle, and its secondary application (by implication) in covering a full 24-hour cycle, a range of extended definitions has been suggested.

An attempt has been made below to list the proposed extended definitions of יוֹם roughly in order, from less specific time frames to more specific time frames, and with increasing length of time frame. Phrases having equivalent meaning are grouped together. Scholars describe יוֹם in the following terms:

- “used ‘figuratively’” (Fields 1976, 175), “not literal days” (Hayward [1985] [1995] 2005, 164);

- “used figuratively of opportune time … [if] limited by some … qualifying statement” (Dake 2001);8

- “time period other than day” (Bradley and Olsen 1984, 299), “another sense [other] than ‘twenty-four hours’” (Kelly 1997, 108);

- “a point of time” (Lewis and Demarest 1990, 44), “a specific point of time” (Stambaugh 2003, 52);

- “more time than a standard day” (Craigen 2008, 201), “periods of time greater than twenty-four hours” (Kulikovsky 2009, 149), “figuratively … to denote a period of time longer than twenty-four hours” (D. A. Young 1977, 83);

- “time in a general sense” (Morris 1974, 223), “a general or vague concept of time” (Stambaugh 2003, 52);

- “a period of time” (Longman III 2005, 104), “some period” (Mathews 1996, 149);

- “a period of time … [if] limited by some … qualifying statement” (Dake 2001);9

- “with a preposition, as in beyôm, it is an indefinite temporal clause” (Craigen 2008, 201), and many other scholars state or imply the same;

- “the whole period of creation” (Hayward [1985] [1995] 2005, 163), “all the days [of creation] together” (Williams 1988, 108), and many other scholars state or imply the same;

- “an occasion when God acts” (Hayward [1985] [1995] 2005, 163), “a time of divine visitation or judgment” (Oden 1987, 234);

- “days of God [having] no human analogies” (Kidner 1967, 56);

- “a longer period of time, during which certain revealed purposes of God are to be accomplished” (Scofield and English 1967, 1);

- “a portion of the year” (Kelly 1997, 108);

- “a particular season or time” (Fischer 1990, 17; citing WOTWS [1870] 1990, 109);

- “a year” (Lewis and Demarest 1990, 44), “a period of a year” (Stambaugh 2003, 52);

- “an indefinite period of time” (Beall 2017, 159; Oden 1987, 234), “a period of unspecified length” (Collins 2006, 128), “indefinite periods of time” (Feinberg 2006, 592), “time of undesignated length” (Fischer 1990, 15), “unmeasured period of time” (Hamilton 1990, 53; Sarfati 2015, 119, citing Hamilton 1990, 53), “periods of indefinite length” (Harris 1995, 22), “a period of time … of undefined length” (Lennox 2011, 51), “indefinite time” (Morris 1976, 54, 56), “periods of indeterminate time” (Munyon 1995, 231);

- “stages of unspecified length” (Archer 2007, 159);

- “a more extended space of time” (Archer 1984, 328), “a longer period of time” (Grudem 1994, 293; Strauss 2017b, 169, citing Scofield 1967, 1), “a long ‘time’” (Lewis and Demarest 1990, 44), “longer periods of time” (Newman and Eckelmann Jr. 1977, 61), “a long but finite time period” (Ross 2017, 162; Ross and Archer 2001, 125);

- “indefinite or considerable length of time” (Blocher [1979] 1984, 44), “a period of time, however short or long … even ages” (Williams 1988, 108);

- “epoch … season … time” (Gentry Jr. 2016, 96; citing Dabney [1878] 1972, 255);

- “epochs or long periods of time” (Erickson 2013, 351), “a long time; a whole period” (Fischer 1990, 17; citing WOTWS [1870] 1990, 109), “a long period of time” (Geisler 2003, 642), “era” (Hamilton 1990, 53; Sarfati 2015, 119, citing Hamilton 1990, 53), “age” (Irons and Kline 2001, 250), “ages … ‘epoch’” (Kidner 1967, 56), “generations—eons, long historical ages” (Schwab 2017a, 137);

- “unusually long period of time, even up to a millennium” (Hamilton 1990, 53; Sarfati 2015, 119, citing Hamilton 1990, 53);

- “[Hosea’s] ‘third day’ … possibly … a year [or] … the Millennium” (Hayward [1985] [1995] 2005, 164);

- “the coming messianic age” (Blocher [1979] 1984, 44);

- “God’s ‘day’ … as a thousand years” (Mathews 1996, 149);

- “an epoch that extends [from the seventh day] onward into eternity” (Lennox 2011, 50), “forever” (Harris 1995, 23; Schwab 2017a, 137).

What is immediately striking is the wide range of expression given to a whole spectrum of meanings, from “a specific point of time” (Stambaugh 2003, 52) right up to “forever” (Harris 1995, 23; Schwab 2017a, 137; similarly, Lennox 2011, 50). Such semantic flexibility contrasts markedly with most lexical entries for יוֹם, though it accords with the definitions found in TWOT (1980) and WOTWS ([1870] 1990).

Table 4 summarizes and merges all the types of non-literal ‘day’ advocated by scholars whose writings were examined in this study (see Appendix 1).10 Most are of indefinite duration. However, there are three firm proposals for non-literal days of limited duration:

- a ‘day’ of creating/making lasting a week (or longer);

- a ‘day’ of God’s speaking with Moses on Mount Sinai lasting forty days and forty nights;

- a ‘day’ in YHWH’s eyes lasting a millennium.

We will briefly discuss each of these three proposals in turn, before looking at days of indefinite duration.

| Referent | Proposed Vlaue | Reference(s) | Advocates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite Limited Duration (in sequence of increasing length) | |||

| ‘day’ of making/creating | 6 days (whether literal days or longer days) | Genesis 2:4 (Schwab includes 5:1 and suggests that in both instances “day” is “a synonym for ‘generations’—eons, long historical ages”) | Archer, Beall, Craigen, Feinberg, Fischer, Geisler, Grudem, Harris, Irons & Kline (?), Lennox, Lewis & Demarest, Newman & Eckelmann, Schwab, Strauss, Williams |

| ‘day’ of God’s speaking with Moses on Mount Sinai | 40 days and nights | Numbers 3:1 | Williams |

| ‘day’ in YHWH’s eyes | millennium | Psalm 90:4; 2 Peter 3:8 | Blocher, Geisler, Hamilton, Irons & Kline, Kelly, Kidner, Lewis & Demarest, Mathews, Ross, Sarfati, Williams |

| Indefinite Limited Duration (in alphabetical order) | |||

| ‘day’ of adversity | period | Proverbs 24:10; Ecclesiastes 7:14 | Dake, Grudem |

| ‘day’ of affliction | period | Jeremiah 16:19 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of battle | (indefinite) period | Proverbs 21:31 | Feinberg, Grudem |

| ‘day’ of calamity | period | Jeremiah 18:17 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of Christ | period | Philippians 2:16 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of darkness | period | Joel 2:2 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of death | period | Ecclesiastes 8:8 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of distress | (indefinite) period | Proverbs 24:10; Obadiah 14 | Dake, Feinberg |

| ‘day’ of evil/disaster | (indefinite) period | Jeremiah 17:17–18 | Dake, Oden |

| ‘day’ of exodus from Egypt | indefinite period | Jeremiah 11:4–7 | Oden |

| ‘day’ of gladness | period | Song of Solomon 3:11 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of God | period | 2 Peter 3:12 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of God Almighty | period | Revelation 16:14 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of grief | period | Isaiah 17:11 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of harvest | (indefinite) period | Proverbs 25:13 | Archer, Feinberg, Grudem |

| ‘day’ of His anger/wrath | (indefinite) period | Job 20:28; Psalm 110:5; Proverbs 11:4; Romans 2:5; Revelation 6:17 | Dake, Feinberg, Grudem, Lewis and Demarest, Oden, Ross and Archer |

| ‘day’ of His coming | period | Malachi 3:2 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of His fierce anger | period | Isaiah 13:13 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of His indignation | period | Ezekiel 22:24 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of judgment | period | 2 Peter 2:9 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of power | period | Psalm 110:3 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of prosperity | (indefinite) period | Ecclesiastes 7:14 | Dake, Feinberg, Grudem |

| ‘day’ of redemption | period | Ephesians 4:30 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of salvation | period | 2 Corinthians 6:2 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of sickness | indefinite period | Jeremiah 17:16 | Oden |

| ‘day’ of temptation | period | Psalm 95:8 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of the Son’s revelation | period | Luke 17:30 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of trouble | (indefinite) period | Psalm 20:1; 102:2 | Dake, Feinberg, Grudem |

| ‘day’ of vengeance | period | Isaiah 61:2 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of visitation | period | 1 Peter 2:12 | Dake |

| ‘day’ of/for YHWH/the Lord | (long, indefinite) period, known only to God | Isaiah 2:12, 21; 13:6, 9; Jeremiah 46:10; Ezekiel 13:5; 30:2, 3; Joel 1:15; 2:1, 31; Amos 5:18, 20; Obadiah 15; Zephaniah 1:14–18; Zechariah 14:7; 1 Thessalonians 5:2; 2 Peter 3:10 | Archer, Collins, Dake, Feinberg, Geisler, Grudem, Hayward, Lennox, Lewis & Demarest, Longman III, Newman & Eckelmann, Oden |

| “(in) that ‘day’” | messianic age | Isaiah 2:11; 4:2; Amos 9:11; Zechariah 12:3; 2 Thessalonians 2:3 | Blocher, Kidner, Lewis & Demarest, Oden |

| Hosea’s third ‘day’ | perhaps a year or a millennium | Hosea 6:2 (cf. 2 Kings 19:29) | Hayward, Irons & Kline, Ross, Ross & Archer |

| Jesus’ three ‘days’ | figurative | Luke 13:32 | Hayward |

| the last ‘day’ | indefinite period | Lennox | |

| Indefinite Unlimited Duration | |||

| ‘day’ of God’s Sabbath rest | indefinite, forever | Psalm 95:11; John 5; Hebrews 4:1–11 | Harris, Lennox, Mathews, Ross, Schwab |

A Day Equating to a Week

Archer (1984, 327) speaks for many when he asserts, “It is perfectly evident that yōm in Genesis 2:4 could not refer to a twenty-four hour day.” Together with Ross he affirms, “Here the word day refers to all six creation days … Obviously, then it refers to a period longer than 24 hours” (Ross and Archer 2001, 147). Mathews (1996, 149) agrees, “Yôm … is used as a temporal expression for the entire creative period of six days in the tôlĕdôt section …, ‘in the day they were created.’” Fischer (1990, 16) states, “In Genesis 2:4 … ‘day’ [is] a coverall to apply to the previous six days of creation.” Craigen (2008, 201), while advocating a literal reading of the creation days in Genesis 1, admits, “Since in the case of Genesis 2:4 the immediate context focuses on the creation of the heavens and the earth and everything in them, then ‘in the day’ here covers the whole six days of creation.” Geisler (2003, 643) comments, “‘The day’ [in Gen 2:4] means six ‘days,’ which indicates a broad meaning of the word day in the Bible, just as we have in English.” Similarly, Feinberg (2006, 593) writes, “Since ‘day’ in this verse refers to all six days of creation, plus the events of Gen 1:1 (creation ex nihilo), it cannot in 2:4 mean one twenty-four-hour solar day. The different uses of yôm show that the days of Gen 1 could be literal twenty-four-hour days, but they could just as easily be much longer.” Other scholars advocating this week-long ‘day’ include Grudem (1994, 293), Strauss (2017b, 169), Williams (1988, 108), and Young (1982, 58).

A Day Equating to Forty Days

With regards to the second suggestion, J. Rodman Williams (1988, 108) alone asserts that, in Numbers 3:1, “‘the day that the Lord spake with Moses’ … lasted forty calendar days and nights!” However, Moses’s extended time on Mount Sinai was recorded in Exodus 34:28, whereas more recently, Numbers 1:1 opens with the immediate and very specific temporal context, “YHWH spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, in the tent of meeting, on the first day of the second month, in the second year after they had come out of the land of Egypt, saying” (Numbers 1:1, ESV*). So יוֹם in Numbers 3:1 would appear to refer to the precise date mentioned in Numbers 1:1.

A Day Equating to a Millennium

Many scholars advocating a relatively broad semantic range for יוֹם—including Blocher, Geisler, Hamilton, Irons and Kline, Kelly, Kidner, Lewis & Demarest, Mathews, Ross, Sarfati, and Williams—point to Psalm 90:4 or 2 Peter 3:8 as evidence that “day” can equate to a long period of time, such as a millennium see discussion on pages 106–107). A few refer to Hosea 6:2, including Hayward ([1985] [1995] 2005, 164), who observes,

In Hosea 6:2 it says that ‘on the third day he [God] will raise us [Israel] up.’ Long before the present controversy, commentators were pointing out that this ‘third day’ was evidently figurative, and was quite possibly a reference to the events described in 2 Kings 19.29, in which case it would represent a year. Some expositors even equated Hosea’s ‘third day’ with the Millennium.

Similarly, Ross and Archer (2001, 148) note, “For centuries Bible commentators have noted that the term days in [Hosea 6:2] … refers to a year, years, a thousand years, or maybe more.”11 However, McComiskey (2009, 88), in his commentary on Hosea, though not specifying precisely what “days” in 6:2 equates to, intimates that it represents a relatively brief period:

The period of three days represents a short while…. Hosea assures the people that God will respond to their repentance in a short time. He designates this brief period “after two days” and says that the nation will arise on the “third day.” … The point is that when the people respond in sincerity to God, his response to them will be quick; they will have to wait only a short time for relief.

Days of Indefinite Limited Duration

Regarding the instances in which יוֹם is said to indicate a period of indefinite limited duration, Finis Jennings Dake (2001)12 lists “28 Kinds of Days in Scripture” that he believes equate to “a period of time.” His list is by far the longest of its kind among the works studied in this thesis. Several entries, e.g., “day of darkness” (Joel 2:2), relate to the special Day of YHWH, which many scholars—including those who read יוֹם literally in the creation account—believe to be figurative. For example, Feinberg (2006, 592) states, “‘The day of LORD,’ … in most cases is an eschatological day whose length only God knows (Isa 13:6, 9; Joel 1:15; 2:1; Amos 5:18; Zeph 1:14).” Williams (1988, 108) speaks for many when he writes, “Many apocalyptic passages in the Bible … speak of a coming ‘day of the Lord’ in which a great number of events will occur. There is little or no suggestion that everything will occur in twenty-four hours.” Hayward ([1985] [1995] 2005, 163) asserts, “The expression ‘a (the) day of the Lord’ is used many times in both Old and New Testaments as a figure of speech. It means ‘an occasion when God acts’ and gives no indication of how long that action by God will last.” Similarly, Newman and Eckelmann Jr. (1977, 74) regard “day of the Lord” in many places as an example of an exception to the usual meaning of יוֹם. They reason, one cannot “prove that yom, when used with a number, takes on the more restricted idea of a twenty-four-hour day. Zechariah 14:7, it appears, speaks of the day of the Lord as a continuing period of time, and uses exactly the same Hebrew construction as is used for the ‘first day’ in Genesis 1:5” (61). Ross and Archer (2001, 125) state, “The Hebrew terms yôm (singular) and yamim (plural) often refer to an extended time frame. Perhaps the most familiar passages are those referring to God’s ‘day of wrath.’”

While many scholars would agree with Dake about the figurative nature of יוֹם יהוה (and related phrases), some of the entries in his list find less support, including “day of prosperity” and “day of adversity” in Ecclesiastes 7:14. Together with Feinberg, and Grudem, Dake (2001, 1040) sees “day of prosperity” here as referring to a period of time.13 In the same verse, Grudem (1994, 293) also regards “day of adversity” as a period. Some modern EVV also evidently prefer this reading. For instance, the NIV has “when times are good” and “when times are bad,” respectively. Most other EVV render both phrases with the definite article, viz., “the day of prosperity,” and “the day of adversity” (including, ESV, NRSV, NKJV, KJV, NASB, HCSB, JPS). The use of the definite article in such a context, implies a generic sense that is somewhat akin to the idea of “a period.” However, the Hebrew phrases lack the definite article, viz., יוֹם טוֹבָה (“a day of good/prosperity”), and יוֹם רָעָה (“a day of evil/distress/calamity”).

Days of Indefinite Unlimited Duration

A few scholars maintain that “day” in the Bible can even refer to an indefinite unlimited timeframe, viz., “forever.” For example, Harris (1995, 23; underlining added) argues that the seventh day “rest of God is cited in Ps. 95:11 as lasting until Joshua’s time and is further interpreted in Heb. 4:8–11 as lasting forever.” Schwab (2017a, 137; underlining added) asserts, “The Hebrew word for ‘day’ can mean any number of things. Genesis 2:4 reads, ‘In the day that God created the heavens and the earth.’ There and in 5:1, ‘day’ seems to be a synonym for ‘generations’—eons, long historical ages. Day Seven does not have an evening and a morning and seems to go on forever.” Lennox, like many scholars, sees the seventh day of the creation account as distinct from the previous six days, especially given the absence of the evening-and-morning formula. He reasons,

The omission is striking and calls for an explanation. If, for instance, we ask how long God rested from his work of creation, as distinct from his work of upholding the universe, then Augustine’s suggestion, that God sanctified the seventh day by making it an epoch that extends onward into eternity, makes good sense; and this is followed by many commentators. (Lennox 2011, 50; underlining added)

Lines of Argument in Support of a Non-Literal Interpretation of יוֹם in Genesis 1

A variety of argumentation is used in support of a non-literal interpretation of יוֹם in Genesis 1. In addition to the numerous points presented in Appendix 1, see, for instance, the key headings listed in Geisler (2003, 642–644), Ross (2017, 162–163), and Ross and Archer (2001, 144–153). Table 5 presents the most frequently used arguments encountered in this study, in approximately descending order of use.

| 1 |

The seventh day cannot be an ordinary day since it does not conclude with the formula, “and there was evening, and there was morning,” and Hebrews 4 indicates that it is an ongoing ‘day’ e.g., “The seventh day, the day of God’s rest, is still going on and is therefore a long period of time. The fact that it does not say of the seventh day, as it does of the other six, that ‘there was evening and there was morning—the seventh day,’ was viewed as one clear indication that the seventh day was never terminated. Further, New Testament passages such as Hebrews 4 gave further credence to the continuing existence of God’s Sabbath. If the seventh day was a long period of time then it is also clear … that the preceding six days might also legitimately be treated as long periods of time of indeterminate length” (Young 1982, 59) |

| 2 |

The sixth day is too long to be a normal-length day e.g., “The sixth day includes so many events [Gen 2:15-25] that it must have been longer than twenty-four hours…. If the sixth day is shown by contextual considerations to be considerably longer than an ordinary twenty-four-hour day, then does not the context itself favor the sense of day as simply a ‘period of time’ of unspecified length?” (Grudem 1994, 294) |

| 3 |

The sun was not created until the fourth day, so ‘day’ cannot be literal prior to this e.g., “Even a superficial reading of Genesis 1 should lead the interpreter to question whether the Hebrew word yom (day) should be understood as a twenty-four hour day. After all, a twenty-four-hour day is defined by the alternation of sun and moon. But these are not even created until the fourth ‘day’!” (Longman III 2005, 104) |

| 4 |

יוֹם is used elsewhere in the HB with a non-literal meaning, including to refer to an indefinitely long period e.g., “There are many indications within the text of Scripture to support the belief that the creation ‘days’ were longer than twenty-four hours… [the first being that] the word day (yom) often means a long period of time [Ps 90:4; Joel 2:31; 2 Pet 3:10]” (Geisler 2003, 642) |

| 5 |

יוֹם has two or three different meanings in the creation account, viz., twelve hours (Gen 1:5a) and/or twenty-four hours (Gen 1:5b), and six days (Gen 2:4) e.g., “The … understanding of the days … [as] 24-hour periods … is … rather unlikely [because] the word ‘day’ … is used in several different ways in the Genesis 1:1–2:4 passage. First, it refers to the light that was separated from darkness … (1:5). Second, it refers to light and darkness together … (also 1:5). Third, it refers to all the days together … (2:4 …)” (Williams 1988, 108) |

| 6 |

Key church fathers, like Augustine, interpreted the days figuratively e.g., “Augustine held a nonliteral interpretation of the days, and he was followed by Anselm, Peter Lombard, and others…. No one can deny that nonliteral approaches to the creation days have a venerable place in the history of Christian interpretation” (Irons and Kline 2001, 219) |

| 7 |

The creation account is unique, and therefore it is illegitimate to interpret יוֹם in Genesis 1 in light of its use elsewhere in Scripture e.g., “There is no other place in the Old Testament where the intent is to describe events that involve multiple and/or sequential, indefinite periods of time. If the intent of Genesis 1 is to describe creation as occurring in six, indefinite time periods, it is a unique Old Testament event being recorded…. [Arguments for the use of ‘yom’ as a normal day] elsewhere in the Old Testament cannot be given as unequivocal exegetical significance [—and constitute a common fallacy—] in view of the uniqueness of the events being described in Genesis 1 (i.e., sequential, indefinite time periods)” (Bradley and Olsen 1984, 299) |

| 8 |

The literary style, especially the arrangement of the days, favors a figurative interpretation e.g., “The whole of Genesis 1 [has] a surreal quality … Perhaps Moses dreamed the chapter or saw it in a prophetic vision. Hence it is symbolic. Or maybe God took a week to reveal it. Thus Moses lived through the six days, and they are not a timescale for creation at all. The best explanation is that the seven days are a literary device” (Schwab 2017b, 166) |

| 9 |

Scientific evidence, especially geology, contradicts a literal interpretation of days e.g., “Ultimately, responsible geology must determine the length of the Genesis days, even as science centuries earlier settled the issue of the rotation of the earth about the sun” (Lewis and Demarest 1990, 29) |

| 10 |

יוֹם is the only, or most appropriate, Hebrew word that could have been used to designate long periods of time e.g., “Biblical Hebrew has no word other than yôm to denote a long timespan” (Ross and Archer 2001, 125) |

| 11 |

The lack of uniformity in the syntax of the days—viz., “day one,” “a second day,” “a third day,” “a fourth day,” “a fifth day,” “the sixth day”—suggests a non-literal reading of the creation account e.g., “The presence of the article indicates that the final two days are special … This point of grammar may … be a signal to us … There is … [a] possibility … that the writer did not intend us to think of the first six days as days of a single earth week, but rather as a sequence of six creation days … that might well have been separated by long periods of time” (Lennox 2011, 53–54) |

Most Common Lines of Argument